Reading time: 6 minutes

Nicole Bowens, PhD

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is currently rising in adults aged 20 to 49 years.1 Increasing accessibility to screening may help improve early detection for this population. Liquid biopsy is one method that may accomplish this goal. Additionally, liquid biopsy may also help to improve outcomes after a cancer diagnosis.

In the United States, CRC is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in both men and women and the leading cause of cancer death in men under 50 years old.2 Over the past decade, cancer diagnoses have been rising for both men and women under 50 years old. Additionally, an increasing percentage of these cancers have spread beyond the colon and rectum to nearby lymph nodes or tissues.1 The American Cancer Society estimated that approximately a quarter of these younger patients with CRC have stage IV disease at initial presentation.2

Why is the incidence of CRC increasing in younger people?

The reasons for the increased rate of early-onset CRC is not yet fully understood. Some potential explanations under research are rising rates of obesity and sedentary lifestyles.3 ,4 Indeed, over half of CRC cases and deaths may be attributed to modifiable risk factors which also include smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.5 However, data which may explain the rising trend is currently premature. Further research will be needed to examine potential correlations with concurrent increases in other modifiable risk factors, including type 2 diabetes and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders.3

What changes have been made to tackle this problem?

In response to this trend the American Cancer Society lowered the recommended age to begin screening from 50 to 45 years for a person with average risk. Evidence has indicated that the 45-to-50-year-old group has the same risk of developing CRC as the 50- to 54-year-old group. Despite this change in guidelines, there has been only a modest increase in the amount of screening performed for the younger group.1 It is estimated that 20% of eligible patients aged 45 to 49 years received screening for CRC in 2021.6 These low screening rates indicate an unmet need to improve access to screening and implementation of recommended practices.

Increasing screening rates is essential to improving outcomes for people with early-onset CRC. When CRC is detected before symptoms appear, there is a 74% decrease in the risk of death.7 The current standard-of-care screening methods for CRC are colonoscopy and fecal-based testing. Colonoscopy is currently considered the gold standard. However, it is the most invasive, can be costly, and is generally not convenient for many patients. The fecal-based tests are less invasive but require the patient to prepare a stool sample, which may reduce adherence.8 Unfortunately, the fecal-based tests are underutilized in younger patients.6

How might blood-based assays improve screening rates?

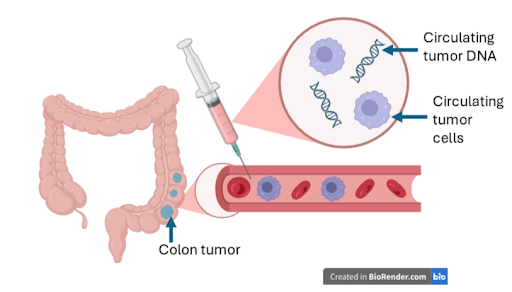

Liquid biopsy is a type of blood-based assay in which elements in the blood that come from cancer cells are identified, including circulating tumor cells, circulating noncoding RNA, and circulating tumor DNA. It is a noninvasive technique that can be performed alongside other routine blood tests.8 Because it is non-invasive, does not require any sample prep on the part of the patient, and can be performed at the same time as other routine tests it may be more accessible as a CRC screening method.10 Liquid biopsy has also shown utility for other types of cancers including breast and lung. While blood-based assays have been available to guide treatment for a number of years, more recent screening applications have begun to enter limited clinical use, with ongoing evaluation in broader screening programs. Use of these tests in clinical practice is not yet fully established.9

In a national survey of adults who were 40 to 75 years old, at average risk for CRC, and not up-to-date with CRC screening, were asked which characteristics of screening tests were the most important to them for test selection. More than half (57.7%) preferred a blood-based assay, in comparison with 29.3% who preferred a stool-based test, and 12.9% who preferred colonoscopy.11 These results suggest liquid biopsy could increase screening rates among all age groups, including those aged 40 to 49 years.

Are there other benefits to liquid biopsy?

The benefits of liquid biopsy extend beyond detection and diagnosis. Because it is less invasive, it is easier to repeat and could therefore be used to determine cancer progression and treatment effectiveness with less treatment burden than biopsy. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is the component that has provided the greatest support for the utility of liquid biopsy.

When ctDNA is detected either before or after treatment, outcomes tend to be worse. Patients who tested positive for ctDNA before surgical resection were more likely to experience recurrence and have a shorter remission period.l2 Patients who were positive for ctDNA after surgery were also at higher risk for recurrence and had lower overall survival rates.9

A similar correlation was also found between ctDNA levels and outcomes after treatment with chemotherapy. In one study patients with ctDNA levels that remained high or increased after treatment started had shorter overall-survival periods. In another study, patients with ctDNA that decreased over the course of treatment had longer progression-free survival periods.10

One of the benefits of ctDNA over other surveillance modalities is a higher sensitivity to detect recurrence. CtDNA was also able to detect recurrence after surgery 10 months sooner than either CT scan or the commonly used blood-based tumor marker carcinoembryonic antigen.12

What is the future of liquid biopsy?

Given its prognostic ability, the next frontier for ctDNA may be guiding therapeutic decisions. One potential method would be to determine whether or not patients would benefit from further treatment. The presence of ctDNA could indicate residual disease and the need for further treatment, while a negative result might support a more conservative approach. Such decisions would need to be made in the context of broader clinical and pathological data. In one clinical trial evaluating patients with stage II colon cancer, when the decision to continue treatment after surgery was guided by ctDNA, the recurrence-free survival rates were the same as the group that received standard-of-care-treatment guidance.10 However, guidelines currently do not recommend for treatment decisions to be made using detection of ctDNA alone.12

Although the data is promising, it is too soon to see whether treatment guidance by ctDNA would improve screening rates and outcomes in clinical practice for patients under 50 years old. With larger, randomized studies, this answer may become clearer for this younger population. Data from a national survey clearly show that people may be more willing to undergo a blood-based assay than the conventional screening modalities.11 Continued data collection will be needed to determine whether liquid biopsy is preferred by the younger age group and if this can translate into higher screening rates.

Header Image Source: Created by author in Biorender.com

Edited by Bethany Cooper

References

- Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. www.doi.org/10.3322/caac.217

- Monahan BV, Patel T, Poggio JL. Stage IV colorectal cancer at initial presentation versus progression during and after treatment, differences in management: management differences for initial presentation versus progression of disease after initial treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2023;37(2):108-113. www.doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1761626

- Stoffel EM, Murphy CC. Epidemiology and mechanisms of the increasing incidence of colon and rectal cancers in young adults. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):341-353. www.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.055

- Sung H, Siegel RL, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(3):e137-e147. www.doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30267-6

- Islami F, Marlow EC, Thomson B, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(5):405-432. www.doi.org/10.3322/caac.21858

- Star J, Siegel RL, Minihan AK, Smith RA, Jemal A, Bandi P. Colorectal cancer screening test exposure patterns in US adults 45 to 49 years of age, 2019-2021. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2024;116(4):613-617. www.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djae003

- Waddell O, Keenan J, Frizelle F. Challenges around diagnosis of early onset colorectal cancer, and the case for screening. ANZ J Surg. 2024;94(10):1687-1692. www.doi.org/10.1111/ans.19221

- Lieberman DA; AGA CRC Workshop Panel. Commentary: liquid biopsy for average-risk colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(6):1160-1164.e1. www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.034

- Patelli G, Lazzari L, Crisafulli G, et al. Clinical utility and future perspectives of liquid biopsy in colorectal cancer. Commun Med (Lond). 2025;5(1):137. www.doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00852-4

- Aggarwal S, Chougle A, Talwar V, et al. Liquid biopsy and colorectal cancer. South Asian J Cancer. 2025;13(4):246-250. www.doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1801753

- Allistair C, Lauzon M, NM Griffin, et al. S538 Assessing Patient Preferences for Blood-Based Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening Tests: Insights from a Conjoint Analysis with Over 1,000 People in the US. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 119(10S):p S372. www.doi.org/10.14309/01.ajg.0001031520.16123.9b

- Krell M, Llera B, Brown ZJ. Circulating Tumor DNA and management of colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;16(1):21. www.doi.org/10.3390/cancers16010021

Leave a comment