Reading time: 4 minutes

Mariella Bodemeier Loayza Careaga

If people were asked to name an organelle inside the cell, the word “mitochondria” would certainly pop into most people’s heads. While we always remember that mitochondria are central to energy production in cells, these bean-shaped organelles also have the amazing ability to move between cells, a phenomenon known as horizontal mitochondrial transfer (HMT).

Since it was first reported in the mid-2000s, HMT has been observed between cells from the same and different types. What’s more, researchers consider mitochondrial transfer a powerful process through which healthy cells can help repair damaged cells, contributing to tissue regeneration and healing processes in disease conditions (1).

Cancer cells can also take advantage of HMT for their benefit. Researchers have shown that cancer cells that import healthy mitochondria from neighboring cells seem more resistant to chemotherapy (2). Additionally, when scientists depleted cancer cells of mitochondria DNA using ethidium bromide — a chemical that accumulates in mitochondria and interferes with the organelle’s DNA replication and transcription — these cells formed tumors more slowly in mice. Interestingly, acquisition of functional mitochondria from host cells re-established this process, fueling tumor formation and progression (3,4).

While evidence shows that cancer cells can steal mitochondria from nearby cells, it was unclear if the opposite process — that is, HMT from cancer cells to healthy cells — could also occur, and what would be the consequences of this form of mitochondrial transfer.

In a recent study, an international team of scientists set out to explore this idea. Their findings show that different cancer cell types can transfer mitochondria to skin cells, and that this form of mitochondrial transfer reprograms healthy cells to support tumor progression (5).

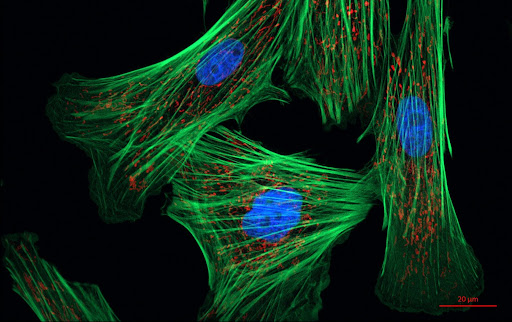

To test if cancer cells could transfer their mitochondria to other cells, the team first co-cultured (grew in the same dish) a malignant carcinoma cell type with skin fibroblasts. They chose fibroblasts because cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are known to modulate cancer metastasis, growth and response to treatment (6). After labeling cancer-derived mitochondria with a green fluorescent dye, the researchers found that the organelles moved from the cancer cells to neighboring fibroblasts through tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) — long, thin structures that mediate cell-to-cell communication and allow exchange of intracellular material.

Interestingly, this phenomenon was not restricted to the malignant carcinoma cell type initially tested; other cancer cell types, including breast cancer and pancreatic cancer cells, also transferred their mitochondria to fibroblasts. The cancer-to-fibroblast mitochondrial transfer was not limited to in vitro settings either. When the team injected cancer cells with labeled mitochondria into the ears of mice and then analyzed the tumors, they also observed HMT between cancer cells and skin cells.

But how do these cancer-derived mitochondria affect fibroblasts’ functions? To address this question, the researchers first analyzed the gene expression and protein profiles of fibroblasts containing cancer-derived mitochondria. These cells showed changes in the expression of molecules involved in immune and stress responses, cellular metabolism and inflammation, as well as higher expression of genes commonly found in CAFs. Fibroblasts bearing cancer mitochondria also secreted factors that facilitated the proliferation and migration of cancer cells, and co-injection of these fibroblasts with cancer cells led to bigger tumors in the ears of mice. These findings suggest that mitochondrial transfer from cancer cells to healthy fibroblasts reprograms these skin cells into CAFs that, in turn, support cancer development and progression.

Next the team set out to identify the molecules that could mediate the cancer-to-fibroblast HMT. They discovered that MIRO2, an enzyme attached to the outer mitochondrial membrane that controls mitochondria trafficking, was highly expressed in the malignant carcinoma cells. When the researchers knocked down MIRO2 in the mitochondria of cancer cells and then co-cultured these MIRO2-depleted cells with fibroblasts, they found that cancer cells couldn’t send their mitochondria to skin cells. Additional experiments revealed that, when co-injected with skin cells into the ears of mice, these MIRO2-deficient cancer cells led to the formation of smaller tumors. Overall, these results further highlight the importance of fibroblasts with functional cancer-derived mitochondria in tumor progression and reveal MIRO2’s key role in the cancer-to-fibroblast mitochondrial transfer.

While researchers knew that cancer cells could steal mitochondria from neighboring cells for their own gain, the new study provides compelling evidence for the opposite process and shows how this form of HMT benefits cancer cells by reprogramming neighboring healthy cells into cancer supporters. By identifying MIRO2 as a key player in this process, the findings also open new avenues for the development of treatments that target this important regulator of mitochondrial trafficking.

Header Image Information & Source: Fluorescence microscopy of fibroblasts (green) in culture. Mitochondria are shown in red. ZEISS Microscopy. Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.

Edited by Karli Norville

References

1. Dong LF, Rohlena J, Zobalova R, et al. Mitochondria on the move: Horizontal mitochondrial transfer in disease and health. J Cell Biol. 2023;222(3):e202211044. doi:10.1083/jcb.202211044

2. Moschoi R, Imbert V, Nebout M, et al. Protective mitochondrial transfer from bone marrow stromal cells to acute myeloid leukemic cells during chemotherapy. Blood. 2016;128(2):253-264. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-07-655860

3. Tan AS, Baty JW, Dong LF, et al. Mitochondrial genome acquisition restores respiratory function and tumorigenic potential of cancer cells without mitochondrial DNA. Cell Metab. 2015;21(1):81-94. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.003

4. Dong LF, Kovarova J, Bajzikova M, et al. Horizontal transfer of whole mitochondria restores tumorigenic potential in mitochondrial DNA-deficient cancer cells. Elife. 2017;6:e22187. Published 2017 Feb 15. doi:10.7554/eLife.22187

5. Cangkrama M, Liu H, Wu X, et al. MIRO2-mediated mitochondrial transfer from cancer cells induces cancer-associated fibroblast differentiation. Nat Cancer. Published online August 28, 2025. doi:10.1038/s43018-025-01038-66. Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(3):174-186. doi:10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1

Leave a comment