Reading time: 4 minutes

Hema Saranya Ilamathi

Cancer is not just a disease of uncontrolled cell growth—it’s a master in cellular manipulation and survival. Scientists have long known that cancer cells behave very differently from normal ones. They reprogram themselves to survive in harsh environments, change the way they use nutrients, and even manipulate their surroundings to gain an edge. One of the most fascinating and alarming ways they do this is by taking advantage of a vital part of our cells: the mitochondria.

Mitochondria are often called the “powerhouses” or batteries of the cell. These tiny structures are responsible for producing the energy that keeps cells alive and functioning. But mitochondria do much more than that—they also play roles in controlling metabolism, regulating cell function, and determining whether a cell should live or die. Because of their central role in cell survival and function, mitochondria are extremely important for cancer cells, which are constantly under stress and need to adapt rapidly to keep growing.

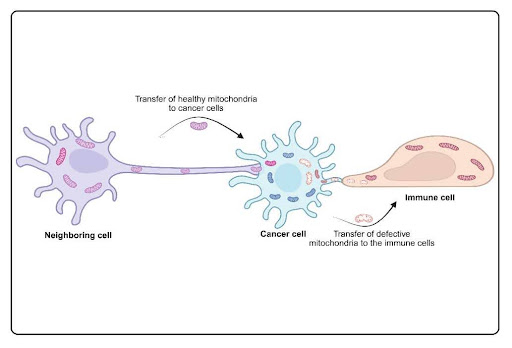

In recent years, scientists have discovered that cancer cells can “borrow” healthy mitochondria from neighboring cells. This process is known as horizontal mitochondrial transfer (HMT). In simpler terms, it means that cells can pass mitochondria to one another, like sharing a battery when one is running low. While this process can be helpful in repairing damaged tissue under normal conditions, cancer cells seem to abuse it for their own gain.

The importance of this discovery became clearer when researchers observed that cancer cells lacking functional mitochondria could not grow tumors. However, when these cells received healthy mitochondria from nearby cells, their ability to form tumors was restored. This indicates that mitochondrial transfer is not just a random occurrence—it may be essential for cancer survival and progression.

HMT doesn’t just help cancer cells survive—it also enables them to resist chemotherapy, become more aggressive, and spread to other parts of the body. For example, when a noninvasive cancer cell receives mitochondria from a more aggressive tumor cell, it can become invasive itself. In other words, mitochondrial sharing among cancer cells can make bad tumors worse.

But this process isn’t one-sided. Cancer cells can also “dump” their damaged mitochondria into nearby healthy cells, including immune cells. This is a sneaky way of offloading cellular waste and avoiding self-destruction. When immune cells take up these damaged mitochondria, it can impair their ability to fight off the cancer. Essentially, the cancer cell both strengthens itself and weakens its enemies.

One of the biggest mysteries in this field is how this transfer happens. Scientists have identified several possible mechanisms, including Tunneling Nanotubes (TNTs; tiny, tube-like bridges between cells), Extracellular Vesicles (EVs; cargo-loaded nanobubbles released by cells), cell fusion (merging of cells), and gap junctions (physical connections between cells). Among them, TNTs are well-studied to regulate HMT, but more research is needed to fully understand which method is most common in cancer and what signals trigger these transfers.

From a treatment perspective, this discovery opens up exciting new possibilities. If scientists can figure out how to block mitochondrial transfer, they may be able to starve cancer cells of the energy and support they need to grow. However, this comes with a caveat: not all mitochondrial transfer is bad. For example, in some cases, immune cells borrow mitochondria from other healthy cells to boost their ability to attack tumors. This adds a layer of complexity to developing therapies—scientists need to find ways to block the bad transfers without stopping the good ones.

This evidence reveals just how connected our cells really are. It also paints cancer in a new light—not just as a group of rogue cells, but as a manipulative player in a larger ecosystem of cellular communication and cooperation. By hijacking these systems, cancer ensures its survival at the expense of its host. Understanding and interrupting these hidden communication networks could be key to developing future cancer therapies. These insights bring us one step closer to treatments that not only destroy cancer cells but also dismantle the support systems they rely on.

So, the next time you hear about “targeted therapies” or “personalized medicine,” remember: the future of cancer treatment might involve cutting off the energy supply that cancer cells steal from their neighbors.

Header & Illustration Image Source: Created by author, using Biorender.com

Edited by Deborah Caldeira

References

1. A. S. Tan, J. W. Baty, L. F. Dong, A. Bezawork-Geleta, B. Endaya, J. Goodwin, M. Bajzikova, J. Kovarova, M. Peterka, B. Yan, E. A. Pesdar, M. Sobol, A. Filimonenko, S. Stuart, M. Vondrusova, K. Kluckova, K. Sachaphibulkij, J. Rohlena, P. Hozak, J. Truksa, D. Eccles, L. M. Haupt, L. R. Griffiths, J. Neuzil, M. V. Berridge, Mitochondrial genome acquisition restores respiratory function and tumorigenic potential of cancer cells without mitochondrial DNA. Cell Metab 21, 81-94 (2015).

2. M. Bajzikova, J. Kovarova, A. R. Coelho, S. Boukalova, S. Oh, K. Rohlenova, D. Svec, S. Hubackova, B. Endaya, K. Judasova, A. Bezawork-Geleta, K. Kluckova, L. Chatre, R. Zobalova, A. Novakova, K. Vanova, Z. Ezrova, G. J. Maghzal, S. Magalhaes Novais, M. Olsinova, L. Krobova, Y. J. An, E. Davidova, Z. Nahacka, M. Sobol, T. Cunha-Oliveira, C. Sandoval-Acuna, H. Strnad, T. Zhang, T. Huynh, T. L. Serafim, P. Hozak, V. A. Sardao, W. J. H. Koopman, M. Ricchetti, P. J. Oliveira, F. Kolar, M. Kubista, J. Truksa, K. Dvorakova-Hortova, K. Pacak, R. Gurlich, R. Stocker, Y. Zhou, M. V. Berridge, S. Park, L. Dong, J. Rohlena, J. Neuzil, Reactivation of Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase-Driven Pyrimidine Biosynthesis Restores Tumor Growth of Respiration-Deficient Cancer Cells. Cell Metab 29, 399-416 e310 (2019).

3. H. Ikeda, K. Kawase, T. Nishi, T. Watanabe, K. Takenaga, T. Inozume, T. Ishino, S. Aki, J. Lin, S. Kawashima, J. Nagasaki, Y. Ueda, S. Suzuki, H. Makinoshima, M. Itami, Y. Nakamura, Y. Tatsumi, Y. Suenaga, T. Morinaga, A. Honobe-Tabuchi, T. Ohnuma, T. Kawamura, Y. Umeda, Y. Nakamura, Y. Kiniwa, E. Ichihara, H. Hayashi, J. I. Ikeda, T. Hanazawa, S. Toyooka, H. Mano, T. Suzuki, T. Osawa, M. Kawazu, Y. Togashi, Immune evasion through mitochondrial transfer in the tumour microenvironment. Nature 638, 225-236 (2025).

4. W. Zhang, H. Zhou, H. Li, H. Mou, E. Yinwang, Y. Xue, S. Wang, Y. Zhang, Z. Wang, T. Chen, H. Sun, F. Wang, J. Zhang, X. Chai, S. Chen, B. Li, C. Zhang, J. Gao, Z. Ye, Cancer cells reprogram to metastatic state through the acquisition of platelet mitochondria. Cell Rep 42, 113147 (2023).

5. L. F. Dong, J. Rohlena, R. Zobalova, Z. Nahacka, A. M. Rodriguez, M. V. Berridge, J. Neuzil, Mitochondria on the move: Horizontal mitochondrial transfer in disease and health. J Cell Biol 222, (2023).

6. V. Marabitti, E. Vulpis, F. Nazio, S. Campello, Mitochondrial Transfer as a Strategy for Enhancing Cancer Cell Fitness:Current Insights and Future Directions. Pharmacol Res 208, 107382 (2024).

Leave a comment