Reading time: 6 minutes

Mikayla Sheild

Cancer is a disease that has long been around, with the earliest known documented human case dating back over 5000 years ago in Ancient Egypt. [1] Millions of people around the world deal with it on a daily basis, whether as a patient themself or as a caregiver of a loved one. In the modern day, there is a range of treatments that exist to help alleviate cancer and even send cancer into remission! Some of these treatments include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplants. [2] Most of these treatment options rely on eradicating cancer cells. But what if you could turn cancer cells back into normal cells?

The Difficulties of Treating Cancer

Cancer results from changes at the genetic level, allowing cells with specific mutations to grow, multiply, and evade cell death. [3] The type of cancer a patient has often guides what treatment healthcare professionals recommend. However, due to its complex nature, this disease can be a challenge to treat. Some of the features that contribute to this difficulty in treating include:

- Heterogeneity: A trait of cancers where cancerous cells may have differing genetic makeup and physical characteristics. These differences can allow for the subpopulations of a specific cancer to evolve and become resistant to treatments. [4]

- Diagnosis limitations: Early detection of some cancers can be difficult because symptoms can be confused for other conditions, or symptoms may not develop at all. [3]

- Suppression of the immune system: Some cancer types are capable of evading or suppressing immune cells. As a result, the disease can progress and worsen in most cases. [5]

- Drug resistance: Occurs when cancer cells innately have or obtain resistance to cancer drugs. This will render treatment with those specific drugs useless to the resistant cancer strain. [6]

- Metastasis: Occurs when cancer spreads to other parts of the body from its initial origin site. The spread of cancer increases the areas in the body that require treatment and may not always be detected before the disease progresses to advanced stages. [3]

Cancer Reversal

Because of the complexity of cancer, it is widely believed that cancerous cells are not able to be turned back into regular cells. This belief comes from the nature of cancer, where the collection of genetic changes had led to cells mutating to achieve outstanding growth rates and simultaneously escape normal cell death. Despite this, there are known instances where tumor cells have reverted, either spontaneously or in research settings, back into cells exhibiting physical traits of normal, healthy cells. [7] This phenomenon is known as cancer reversal!

Cancer reversal was first observed in 1907 by a researcher studying a tumor that began to divide into cells with typical traits or “phenotype.” Another study involving cancer reversal was completed in the 1970s and relied on the use of external chemical compounds to treat leukemia cells. It even found high clinical success in treating patients suffering from that type of leukemia. [7] In the first case, the return to a regular phenotype was believed to have arisen from mutations that negated the malignant mutations. In contrast, the latter case involved direct involvement from researchers. Both of these approaches, however, involved directly influencing how malignant cells could differentiate.

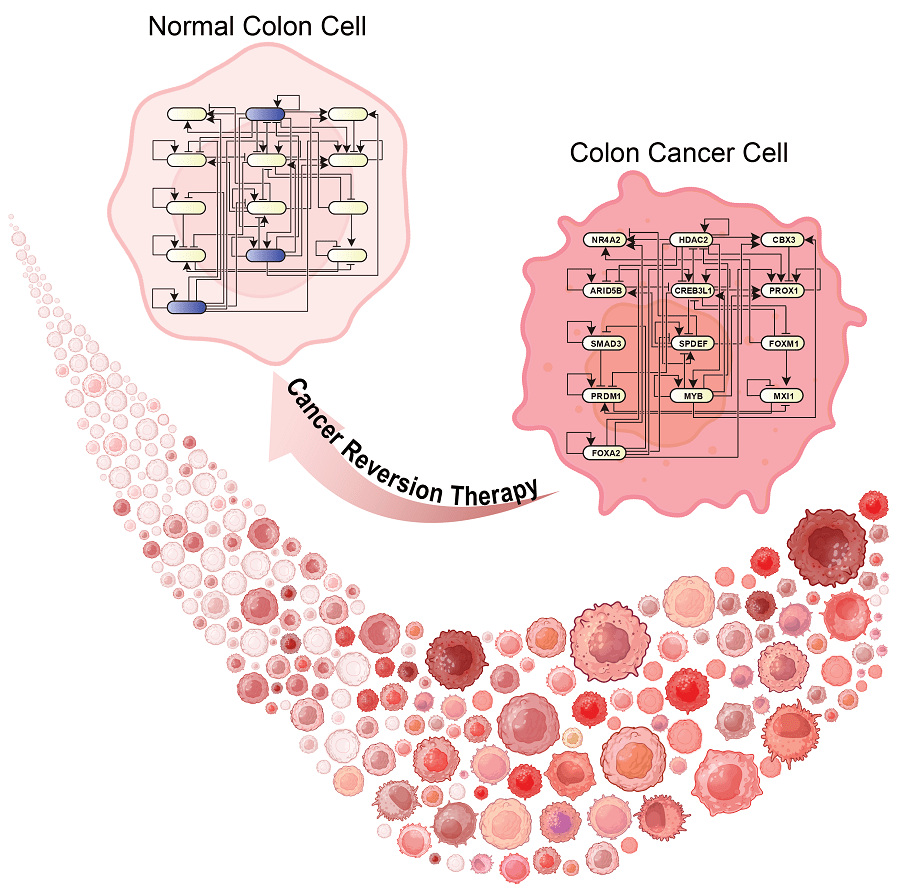

Differentiation is a process that stem and embryonic cells undergo in response to environmental signals that help them specialize for different functions, such as a skin cell or a cardiac cell. Genes are a driving force in this process and play a major role in determining what cell type will develop. [8] By targeting the differentiation abilities of malignant cells, either by internal or external means, you can initiate the reversal of a cancerous cell into a normal cell. This is relatively easy to achieve with liquid cancers, such as in the leukemia study mentioned earlier, but is notably more difficult with solid tumor cancers. The difficulties in reverting solid tumor cells come from the multiple chemical communication pathways that contribute to malignancy. Often, these communication pathways are capable of communicating with each other. [7] This ability of pathways to intercommunicate allows for the cell continue to function and receive messages in the event that a mutation renders a part or whole pathway inactive. However, this also results in an additional resistance to external interference. Identifying the genes that result in the transformation of a normal cell into a malignant one is another difficulty observed in using differentiation-based treatment in solid tumors. [7] This is where the utilization of technology can be helpful.

The Aid of Technology in Research

In late 2024, a research team based in Korea and led by Kwang-Hyun Cho published their results describing how they built a computational framework capable of identifying key regulator genes using single-cell transcriptomic data. This framework is called single-cell Boolean network interference and control, or simply BENEIN. [9] BENEIN was created to utilize and build upon features found in Boolean modelling-based gene regulatory networks (GRNs). Boolean modeling shows how different nodes in a system or network are connected and which state (out of two options, such as on vs. off) each node is in. Because of this, Boolean modeling is used to represent many biological processes, including GRNs. [9,10] However, there are a number of limitations that have been observed with GRNs using Boolean networking, including scaling issues and assuming irregular time intervals. [9]

BENEIN is capable of building these Boolean GRNs, performing statistical analyses, and identifying genes that contribute to the malignancy transition of a normal cell. It is able to construct GRNs based on provided transcriptomic data, yet without requiring additional information first like prior algorithms. [9] Utilizing the BENEIN computational tool, Cho and his team were able to successfully identify 3 master regulator genes that contributed to colon cancer. The team confirmed their findings in triple-knockout vs. control models. Additionally, they tested BENEIN’s abilities in identifying genes contributing to granular cell development in the hippocampus based on mouse transcriptome data. [9] Their findings identified and confirmed key genes that were highlighted in previous studies, showing that BENEIN can aptly predict key genes using single-cell data.

Potential for Clinical Application

Cancer reversal shows promise as a future treatment option, particularly because of its ability to transform harmful cells back into a non-harmful form. It allows patients to avoid the negative side effects of currently used treatment methods, such as chemotherapy and radiation. It is a specific approach that, ideally, will not hurt healthy cells, which helps maintain the patient’s overall health beyond the cancer. Additionally, if utilizing a technology like BENEIN, it can allow for precise treatment unique to each patient by identifying the key genes causing malignancy. There are a few limiting factors, however. One such factor is that the mutations that lead to cancer are often unique to each patient. This can complicate the identification of key genetic contributors. Another difficulty may be the cost and time needed for implementation, since most findings are still new and need further investigation. In spite of this, ongoing research shows promising results that bring us closer to being able to reverse cancer as a form of treatment.

Header Image Source: https://www.rawpixel.com/image/5941554

Figure 1 Image Source: Gong et al. (2025). Advanced Science. DOI: 10.1002/advs.202402132 (Accessed from here: https://engineering.kaist.ac.kr/board/view?bbs_id=news&bbs_sn=17770&page=2&skey=subject&svalue=&menu=9)

Edited by Karli Norville

References

- Di Lonardo, A., Nasi, S., & Pulciani, S. (2015). Cancer: we should not forget the past. Journal of Cancer, 6(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.10336

- National Institute of Health. (n.d.). Types of cancer treatment. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types

- Chakraborty, S., & Rahman, T. (2012). The difficulties in cancer treatment. Ecancermedicalscience, 6, ed16. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2012.ed16

- Jacquemin, V., Antoine, M., Dom, G., Detours, V., Maenhaut, C., & Dumont, J. E. (2022). Dynamic Cancer Cell Heterogeneity: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications. Cancers, 14(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14020280

- Tie, Y., Tang, F., Wei, Y. Q., & Wei, X. W. (2022). Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Journal of hematology & oncology, 15(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01282-8

- Glimcher, L. (2016, December 21). Why do cancer treatments stop working?. Cancer.gov. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/research/drug-combo-resistance

- Shin, D., & Cho, K. H. (2023). Critical transition and reversion of tumorigenesis. Experimental & molecular medicine, 55(4), 692–705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-00969-3

- Ralston, A. & Shaw, K. (2008) Gene expression regulates cell differentiation. Nature Education 1(1):127. https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gene-expression-regulates-cell-differentiation-931/

- Gong, J. R., Lee, C. K., Kim, H. M., Kim, J., Jeon, J., Park, S., & Cho, K. H. (2025). Control of Cellular Differentiation Trajectories for Cancer Reversion. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany), 12(3), e2402132. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202402132

- Kadelka, C., Butrie, T. M., Hilton, E., Kinseth, J., Schmidt, A., & Serdarevic, H. (2024). A meta-analysis of Boolean network models reveals design principles of gene regulatory networks. Science advances, 10(2), eadj0822. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj0822

Leave a comment