Reading time: 6 minutes

Colin Ong

Oncogenic signaling is a key characteristic of cancer cells

Cancer cells, unlike normal cells, exhibit aberrant oncogenic signaling. This aberrant signaling, which is continuously turned on, facilitates the survival and proliferation of cancer cells as well as other hallmarks of cancer1. The term “oncogenic”, an adjective derived from the word oncogene, refers to genes that are prone to cause cancer when mutated. Although a large number of genetic and non-genetic alterations have been identified across different types of cancers, the growth and survival of a particular tumor is probably driven by a few key mutations resulting in the loss of a tumor suppressor or a gain of an oncogene. This phenomenon of dependence on the activity of just one or a few oncogenes for tumor maintenance is known as oncogene addiction2.

Targeted therapy to combat cancer

The discovery that cancer cells exhibit oncogenic signaling and oncogene addiction as a means for survival and proliferation has led to the identification of these oncogenes as targets for therapy. Inhibitors that suppress the oncogenes’ activities have been developed as drugs for cancer treatment. These inhibitors, which are part of the targeted therapy arsenal, include small molecule inhibitors and antibodies that block signaling pathways that mediate cancer cell survival and proliferation. Other targeted therapies include immune checkpoint inhibitors which can boost the host antitumor immune response3.

Long-term administration of these inhibitors to patients often leads to resistance – where the cancer no longer responds to treatment. Cancer cells that display the resistant phenotype have been found to acquire secondary mutations that allow them to reactivate the signaling pathway that was blocked by the inhibitor. Prolonged exposure of cancer cells to targeted inhibitors gives rise to resistance, which suggests the need for different approaches to combat cancer.

Activation of oncogenic signaling in cancer cells comes at a cost

In seeking other vulnerabilities of cancer cells to exploit as potential targets for treatment, researchers have explored and examined the effects of oncogenic signaling that go beyond supporting tumor cell proliferation in cancer cells. One interesting aspect that caught the attention of scientists is the high levels of cellular stress that cancer cells undergo in engaging oncogenic signaling, such as DNA replication stress. In response to the high-stress levels, cancer cells muster stress response pathways to cope with this burden. Thus, cancer cells strike a compromise between achieving elevated proliferation rates and handling manageable stress levels.

Hyperactivation of oncogenic signaling has been demonstrated to be toxic to cancer cells. For instance, DUSP1 and DUSP6 are two enzymes (phosphatases) that suppress mitogenic signaling pathways. Cell division is a highly regulated event. Mitogenic signaling serves to signal the cell to undergo proliferation. Feedback mechanisms in the cell will trigger enzymes like DUSP1 and DUSP 6 to shut down the mitogenic signaling to prevent the cell from continuously dividing. Blocking the activities of both DUSP1 and DUSP6 with chemical inhibitors in cells of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a type of white blood cancer, resulted in DNA damage and cancer cell death4, highlighting the idea that overactivation of oncogenic signaling can lead to cancer cell death.

Hyperactivation of oncogenic signaling and suppressing stress response pathways as a potential cancer therapeutic strategy

Based on these earlier observations on the coupling of oncogenic signaling and stress response pathways in cancer cells, Dias and coworkers hypothesized that overstimulation of mitogenic signaling in cancer cells might result in a dependence on stress response pathways that can then be targeted. To test this hypothesis, they first established that hyperactivation of mitogenic signaling results in the mobilization of stress response pathways. They exposed two colorectal cancer cell lines, namely HT-29 and SW-480 cell lines, to LB-100, a PP-2A (phosphatase) inhibitor, followed by gene knockdown and overexpression as well as RNA analysis to determine which cellular pathways were impacted by the LB-100. LB-100 was shown to activate mitogenic pathways, namely WNT/beta-catenin and MAPK pathways, inflammatory pathways, and stress response pathways. Then the investigators sought to determine which stress response pathway inhibitors/activators could be used as a potent cell death inducer. They treated these cancer cells to a panel of 164 different stress response inhibitors or inducers in the presence of LB-100. This investigation led to the identification of stress response inhibitors that target two proteins, CHK1 and WEE1 kinases, as potent inducers of cell death. The WEE1 and CHK1 kinases play major roles in modulating cell cycle control5.

Dias and colleagues focused their studies on the combination of WEE1 inhibitor, adavosertib, and LB-100, the PP-2A inhibitor. When tested in combination, both drugs displayed strong lethality in comparison to the modest toxicity demonstrated when these drugs were tested individually in both HT-29 and SW-480 colorectal cancer cell lines. Similar synergistic effects of both drugs in inducing cancer cell death were observed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, bile duct cancer, cell lines5.

How does this combination of two drugs kill cells? To understand the mechanisms underlying cancer cell death as induced by LB-100 and adavosertib, Dias and fellow scientists examine the morphology and nuclei of cells stimulated with these drugs using cellular, molecular, and biochemical techniques. Cells treated with both drugs exhibit fragmented chromatids, partial chromatin condensation, defective chromosome alignment, and DNA replication defects. These cellular defects led to apoptosis5.

Compared with the antitumor effects of single drugs, both drugs in combination displayed stronger effects in restraining tumor growth in mouse models of colorectal and cholangiocarcinoma. Drug exposure did not compromise tissue integrity in organs such as liver, heart, lung, and spleen. These drug-treated mice maintained their body weight and no systemic toxicity was detected during treatment. Thus, the researchers have demonstrated that the combination of LB-100 and adavosertib is safe and efficient in treating colorectal cancer and cholangiocarcinoma.

Another aspect that Dias and coworkers addressed was the phenotype of cells that are resistant to the drug combination following chronic drug exposure. Both HT-29 and SW-480 colorectal cancer cell lines were cultured in the presence of both drugs for over four months. Pools of polyclonal cells from both cell lines were selected and analyzed. In comparison to the parental cells, the resistant cells showed less aneuploidy, attenuated mitogenic signaling, and diminished proliferative transcriptional program. Unlike the parental cells, the resistant cells developed relatively small tumors when transplanted into immunocompromised mice over a period of 50 days, suggesting that the resistant cells exhibited a less malignant phenotype5.

In conclusion, Dias and colleagues have demonstrated that the coupling of hyperactivation of oncogenic signaling together with the suppression of stress response pathways can be a potential therapeutic approach. This highly paradoxical strategy reminds us of the saying “Too much of a good thing is a bad thing”. Hyperactivation of oncogenic signaling in cancer cells does not necessarily lead to an elevation in proliferation levels, but it may be detrimental to the survival of these cells. Looking ahead, these findings have opened up new possibilities for treating cancer. Will this regimen work in human cancer patients? The answer awaits further testing and clinical trials. Let’s keep our fingers crossed.

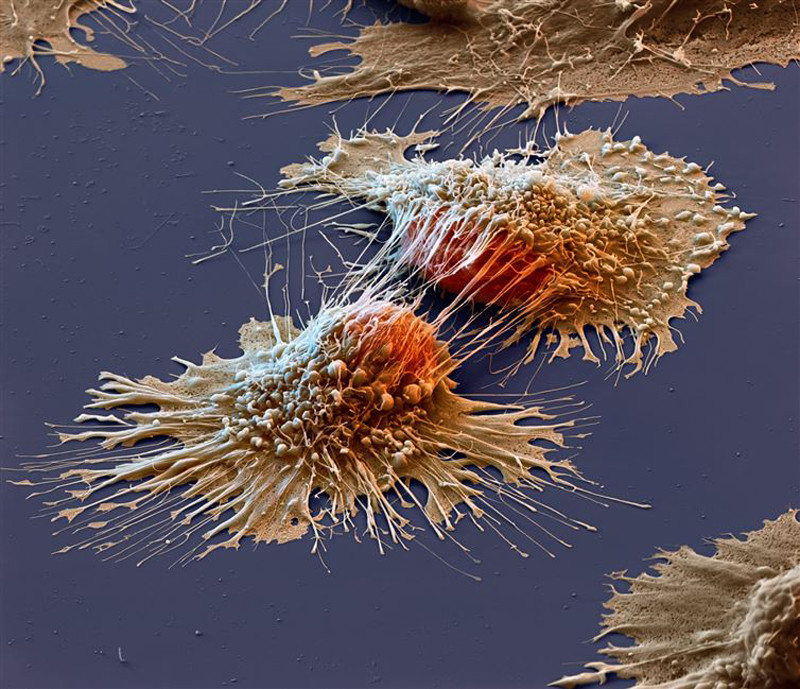

Header Image Source: Levin, S (2020). flickr.com. https://www.flickr.com/photos/samlevin/50263680922

Edited by Karli Norville

References

1. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000 Jan 7;100(1):57-70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9.

2. Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009 Mar 6;136(5):823-37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. Erratum in: Cell. 2009 Aug 21;138(4):807.

3. Min HY, Lee HY. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 2022 Oct;54(10):1670-1694. doi: 10.1038/s12276-022-00864-3.

4. Ecker V, Brandmeier L, Stumpf M, Giansanti P, Moreira AV, Pfeuffer L, Fens MHAM, Lu J, Kuster B, Engleitner T, Heidegger S, Rad R, Ringshausen I, Zenz T, Wendtner CM, Müschen M, Jellusova J, Ruland J, Buchner M. Negative feedback regulation of MAPK signaling is an important driver of chronic lymphocytic leukemia progression. Cell Rep. 2023 Oct 31;42(10):113017. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113017.

5. Dias MH, Friskes A, Wang S, Fernandes Neto JM, van Gemert F, Mourragui S, Papagianni C, Kuiken HJ, Mainardi S, Alvarez-Villanueva D, Lieftink C, Morris B, Dekker A, van Dijk E, Wilms LHS, da Silva MS, Jansen RA, Mulero-Sánchez A, Malzer E, Vidal A, Santos C, Salazar R, Wailemann RAM, Torres TEP, De Conti G, Raaijmakers JA, Snaebjornsson P, Yuan S, Qin W, Kovach JS, Armelin HA, Te Riele H, van Oudenaarden A, Jin H, Beijersbergen RL, Villanueva A, Medema RH, Bernards R. Paradoxical Activation of Oncogenic Signaling as a Cancer Treatment Strategy. Cancer Discov. 2024 Jul 1;14(7):1276-1301. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0216.

Leave a comment