Reading time: 4 minutes

Karli Norville

In 2021, lung cancer was ranked as the number one cause of cancer deaths in the United States (1). The American Cancer Society reports that the 5-year survival rate of all Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) patients is 26% (2). A recent study of the cancer drug Lorlatinib announced a 5-year Progression Free Survival Rate (PFS) of 60%. Given the usually low survival rate of NSCLC, this study presents an exciting and promising new line of treatment for certain NSCLC patients (3).

The Phase III CROWN study (Clinical Trial ID NCT03052608 (4,3)) focused on patients with a positive signature for Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). ALK is a gene that can drive tumor formation if it has inappropriately high expression levels resulting from mutations or rearrangements (fused with other genes). Patients with ALK-positive NSCLC are eligible for ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as first-line therapy. Tyrosine kinases are enzymes involved in many aspects of cell growth and division and are often dis-regulated in cancer, and these inhibitors are designed to disrupt this abnormal signaling (5). Several ALK TKIs are currently available, including Ceritinib and Crizotinib, though tumors often become resistant to these treatments (6). Lorlatinib, the drug investigated in the CROWN trial, is considered a third generation ALK TKI, designed specifically to be able to penetrate into the central nervous system and inhibit known ALK mutant forms that contribute to ALK TKI resistance (7, 8).

In the CROWN study, ALK-positive NSCLC patients were randomly assigned to receive either Lorlatinib or Crizotinib. Crizotinib served as the “standard of care” control for the study, providing researchers the means to compare the efficacy of Lorlatinib with what patients would otherwise receive. The goals of the study were to assess PFS (how long a patient lives without their cancer progressing), Overall Survival (OS – how long a patient survives after starting treatment), objective response, intracranial progression and response, and safety. Each of these metrics provides a quantifiable means by which the investigational drug Lorlatinib can be compared to the standard of care drug Crizotinib.

The most recent publication (3) included findings from the 5-year analysis of the trial. They report that median PFS for patients receiving Crizotinib was 9.1 months, while median PFS for patients on Lorlatinib was not reached by the 5-year analysis timepoint. PFS at 5 years was 60% in the Lorlatinib group and 8% in the Crizotinib group, meaning that 5 years after enrollment, Lorlatinib prevented disease progression in 60% of patients, while Crizotinib did so only in 8%. Although patients on both drugs did respond to the treatment (81% for Lorlatinib and 63% for Crizotinib), the median duration of the response to Crizotinib was only 9.1 months. In contrast, median response duration was not reached for Lorlatinib. This durability of response then, is a key difference between the two drugs.

The development of treatment resistance – where a patient who once responded to a particular therapy no longer does so – is a major problem in treating cancers. To investigate this durability further, the CROWN study analyzed tumor DNA samples taken from patients after they stopped receiving their assigned drug. They found that new ALK resistance mutations were present in patient tumors treated with Crizotinib, but not those treated with Lorlatinib. In addition to the improvements in survival, Lorlatinib provided additional benefits over Crizotinib in preventing the occurrence and progression of brain metastasis.

The study also reports on the safety of the new drug. Adverse Events (AEs) are occurrences of negative health impacts caused by the drug. They are rated on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being mild and 5 resulting in death. Grades of 3 and above are considered Serious Adverse Events and usually result in temporary or permanent treatment discontinuation or dose reduction for the impacted patient (9). 97% of Lorlatinib patients and 94% of Crizotinib patients experienced treatment-related AEs. Lorlatinib did have a higher incidence of Grade 3 and 4 Adverse Events, but many of these events were clinically manageable such that drug discontinuation rates for the two treatment groups were similar. The study authors also report that dose reduction within the first 16 weeks of treatment did not seem to impact the efficacy of Lorlatinib. This suggests that while Lorlatinib shows no general safety improvements over Crizotinib, the dose can be adjusted for some patients who experience Adverse Events to improve their individual experience without jeopardizing their potential benefit from the drug.

This study is promising. Not only did Lorlatinib treatment surpass the efficacy of the study’s comparison drug Crizotinib, but it also resulted in the longest reported PFS of any molecular targeting drug used without other concurrent treatments. In addition to offering hope for some NSCLC patients, it also points to the power of personalized medicine. Only about 5% of NSCLCs are ALK-positive (10), and while this may seem like only a small fraction of total patients, the efficacy of Lorlatinib within this subgroup is astonishing.

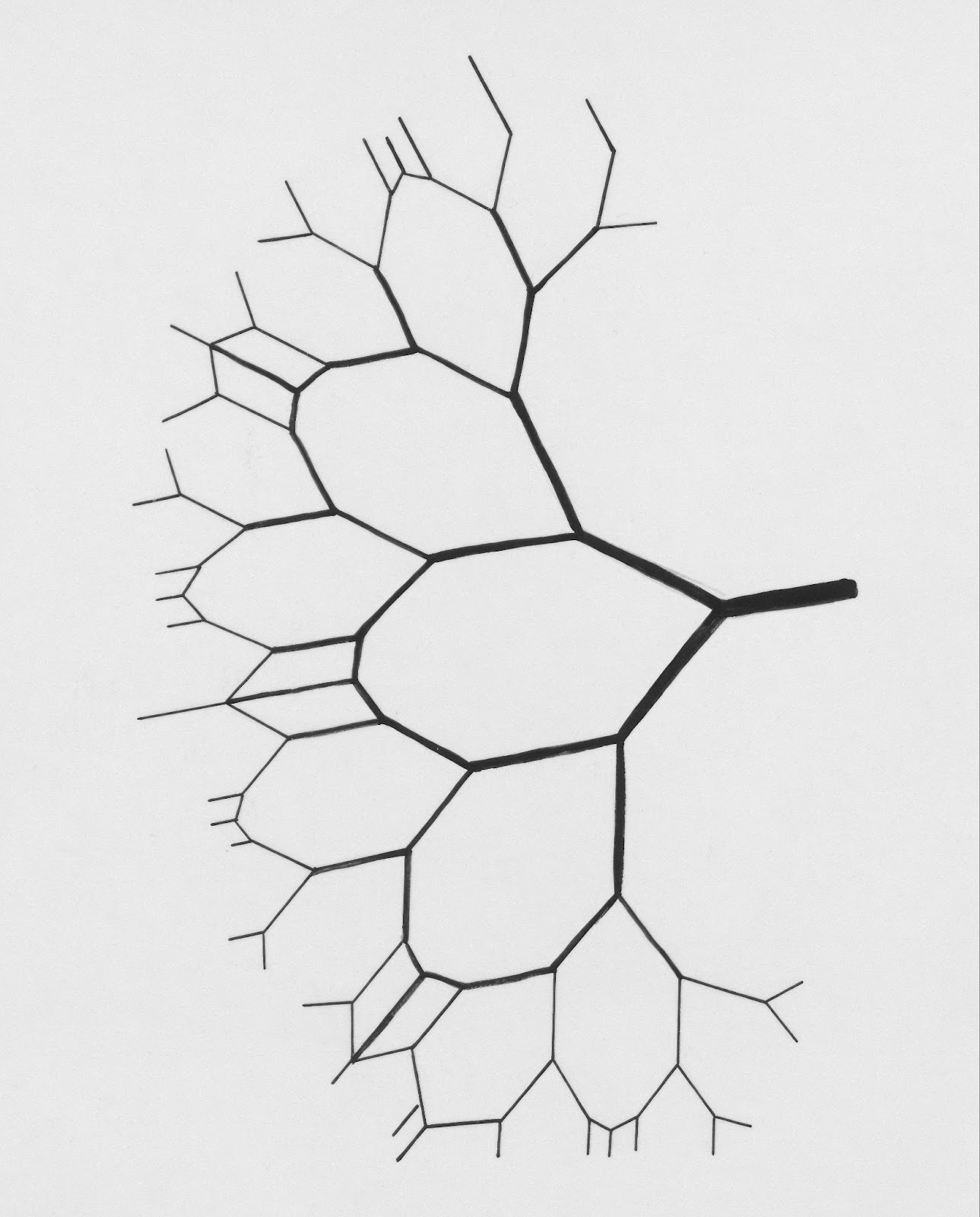

Personalized and precision medicine seeks to tailor a patient’s treatment to their specific cancer, rather than just the broad categories they may fit into. With more knowledge about which cancer types, grouped by even small characteristics or mutation or gene signatures, are good fits for the drugs we have available, we can continue to refine both drug modification and discovery as well as our decision tree for patient treatment. By building up the repertoire of treatments available, physicians and patients can have a large body of therapies to select from. This allows them to build a completely personalized treatment plan on the basis of a patient’s own tumor type, mutations, metastatic profile, and response to previous treatments. The eventual goal of precision medicine is for every patient to have access to therapies that are as well-suited as possible to their cancer – the way Lorlatinib appears to be for ALK-positive NSCLC.

Header Image Source: Unsplash.com, courtesy of Tinkelenberg, J.

Edited by Jessica Desamero

References

- Siegel RL , Giaquinto AN , Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024; 74(1): 12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820 https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21820

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2022-2024. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/2022-cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-fandf-acs.pdf

- Solomon BJ, et al., Lorlatinib Versus Crizotinib in Patients With Advanced ALK-Positive Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase III CROWN Study. JCO 0, JCO.24.00581. DOI:10.1200/JCO.24.00581 https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.24.00581

- A Study Of Lorlatinib Versus Crizotinib In First Line Treatment Of Patients With ALK-Positive NSCLC. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03052608

- https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/tyrosine-kinase-inhibitor

- Holla VR, Elamin YY, Bailey AM, et al. ALK: a tyrosine kinase target for cancer therapy. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2017;3(1):a001115. doi:10.1101/mcs.a001115 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5171696/

- Shaw AT, et al., ALK Resistance Mutations and Efficacy of Lorlatinib in Advanced Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO 37, 1370-1379(2019). DOI:10.1200/JCO.18.02236 https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.18.02236

- Johnson TW, Richardson PF, Bailey S, et al. Discovery of (10R)-7-amino-12-fluoro-2,10,16-trimethyl-15-oxo-10,15,16,17-tetrahydro-2H-8,4-(metheno)pyrazolo[4,3-h][2,5,11]-benzoxadiazacyclotetradecine-3-carbonitrile (PF-06463922), a macrocyclic inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) with preclinical brain exposure and broad-spectrum potency against ALK-resistant mutations. J Med Chem. 2014;57(11):4720-4744. doi:10.1021/jm500261q https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24819116/

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. Published Nov 17, 2017. US Department of Health and Human Services. US National Cancer Institute.

- Arbour KC, Riely GJ. Diagnosis and Treatment of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2017;31(1):101-111. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2016.08.012 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5154547/

Leave a comment