Reading time: 7 minutes

Shan Grewal

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is one of the worst diagnoses a patient can receive today. The median survival of this cancer is just under 15 months, meaning half of patients with GBM will pass away within 1.5 years. Only 4% of patients reach the 5-year mark.1 GBM has left an indelible mark on the field of oncology due to its devastating impact on patients and the immense difficulty in treating it. This article explains GBM, delves into its history, explores why it is so deadly, and unravels the complexities that make it such a challenging tumor to study.

What is GBM?

In short, GBM is a deadly brain cancer. Your brain contains several cell types—the most obvious of which are neurons, the cell units responsible for initiating and spreading electrical impulses. Neurons likely only make up about half of the cells in the brain (it was once believed they only make up 10% of the brain, hence the urban myth that we only use 10% of our brain), while the rest is made up of diverse support cells called glial cells, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia.2 These glial cells have diverse functions in the brain. The most accepted theorem is that GBM is a cancer of these glial cells, although there is very convincing data to suggest that the cells of origin for GBM are neural stem cells.3 The fact that we are yet to pin down a cell of origin for GBM, even with modern technologies, shows how much of an enigma this tumor is.

History of GBM

History provides some perspective on this stalemate. Dr. Rudolf Virchow was the first to identify tumors of glial cell origin in 1863. In 1925, Dr. Harvey Cushing, a neurosurgeon (who also described Cushing Syndrome as a product of pituitary adenomas), and Dr. Percival Bailey, a neurosurgeon, neuropathologist, and psychiatrist, created a classification system for brain tumors, wherein the term glioblastoma was coined. At the time, surgery was the only treatment option available, with a median overall survival of just 3 months. In 1970 (45 years later), radiation was added to the standard of care, increasing median survival to 9 months. Thirty-five years later, in 2005, chemotherapy in the form of temozolomide was introduced to the regimen, increasing median survival to the 15 months we see today. Bevacizumab (commercially known as Avastin), an antibody that blocks blood vessel growth to the tumor, was the most recently approved therapy for GBM in 2007; however, meta-analyses of clinical trials on the treatment showed there was no improvement in overall survival for patients. Therefore, bevacizumab is not part of the routine standard of care for GBM patients today. In all, almost 100 years of GBM research have passed since Drs. Cushing and Bailey first classified this brain tumor. We have only had 4 treatments approved for use in patients with GBM, and we have not yet crossed a median overall survival of 1.5 years.

Why is GBM so deadly?

Several cancer-intrinsic features contribute to its lethality. Unlike many other tumors that form discrete masses, GBM infiltrates surrounding brain tissue. This diffuse spread makes complete surgical removal virtually impossible. Even the most advanced surgical techniques cannot guarantee the elimination of all cancerous cells, leading to high recurrence rates. Additionally, the speed at which GBM progresses leaves little time for intervention, contributing to its high mortality rate. Secondly, GBM is notorious for its genetic complexity. Each tumor is composed of a mosaic of different cell populations, each with its own set of mutations and characteristics. This heterogeneity not only makes it difficult to target the tumor with a single treatment but also allows the cancer to quickly adapt and become resistant to therapies. Not only is there heterogeneity between patients, but also within the patient’s tumor.

On the other side of the coin, tumor-extrinsic factors combine to form a unique tumor niche scarcely seen in other cancers. The brain is protected by a specialized network of blood vessels known as the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which prevents harmful substances from entering the brain. While the BBB is essential for protecting the brain, it also poses a significant obstacle for delivering chemotherapy and other drugs to GBM tumors. Many treatments that are effective against other types of cancer cannot penetrate the BBB in sufficient concentrations to impact GBM. Additionally, the cancer-promoting role of the GBM microenvironment—non-malignant cells surrounding the tumor—has become increasingly appreciated. This microenvironment includes a network of blood vessels that supply the tumor with nutrients, as well as immune cells that are often co-opted to support, rather than attack, the tumor. This supportive microenvironment further enhances the tumor’s ability to survive and spread.

GBM in clinical trials

Clinical features of GBM have made it a graveyard for trials. For instance, unlike other cancers, obtaining tissue samples from GBM patients is highly invasive and risky, given the tumor’s location in the brain. While hematological malignancies can be serially biopsied through the brain marrow, GBM provides limited samples for research and makes it difficult to study the tumor in its natural environment. Conducting clinical trials for GBM is challenging due to the disease’s rapid progression. Patients often have a limited window of time to participate in trials, and the aggressive nature of the tumor makes it difficult to measure the long-term efficacy of treatments. Additionally, the genetic heterogeneity of GBM means that a treatment that works for one patient may not work for another, complicating the design and interpretation of clinical trials. This has unfortunately rendered drug companies hesitant to invest in GBM research due to such high risk with historically no reward to date.

Future of GBM treatments

While the history of GBM is marked by its challenges, there is also hope on the horizon. Advances in genomics, immunotherapy, and precision medicine are opening new avenues for understanding and treating this deadly tumor. For example, researchers used a novel, innovative spatial transcriptomics platform to propose a new model for the spatial organization of GBM.4 Even a chaotic tumor like GBM has some patterns of organization, with a low-oxygen “hypoxic” core, extending to a neurodevelopmental layer as the tumor invades normal brain tissue. Clinical groups have begun to bypass the BBB by injecting CAR-T Cells (immune cells engineered to kill the tumor) into the spinal cords of patients,5 or even directly into the brain,6,7 with Phase 1 trials of such approaches showing safety and promising results.

In conclusion, glioblastoma multiforme is one of the most complex and deadly cancers known to medicine. Its history is a testament to the challenges of studying and treating this formidable disease, but it is also a story of resilience and determination in the face of adversity. As researchers continue to unravel the mysteries of GBM, there is hope that one day, we will find a way to overcome this devastating cancer.

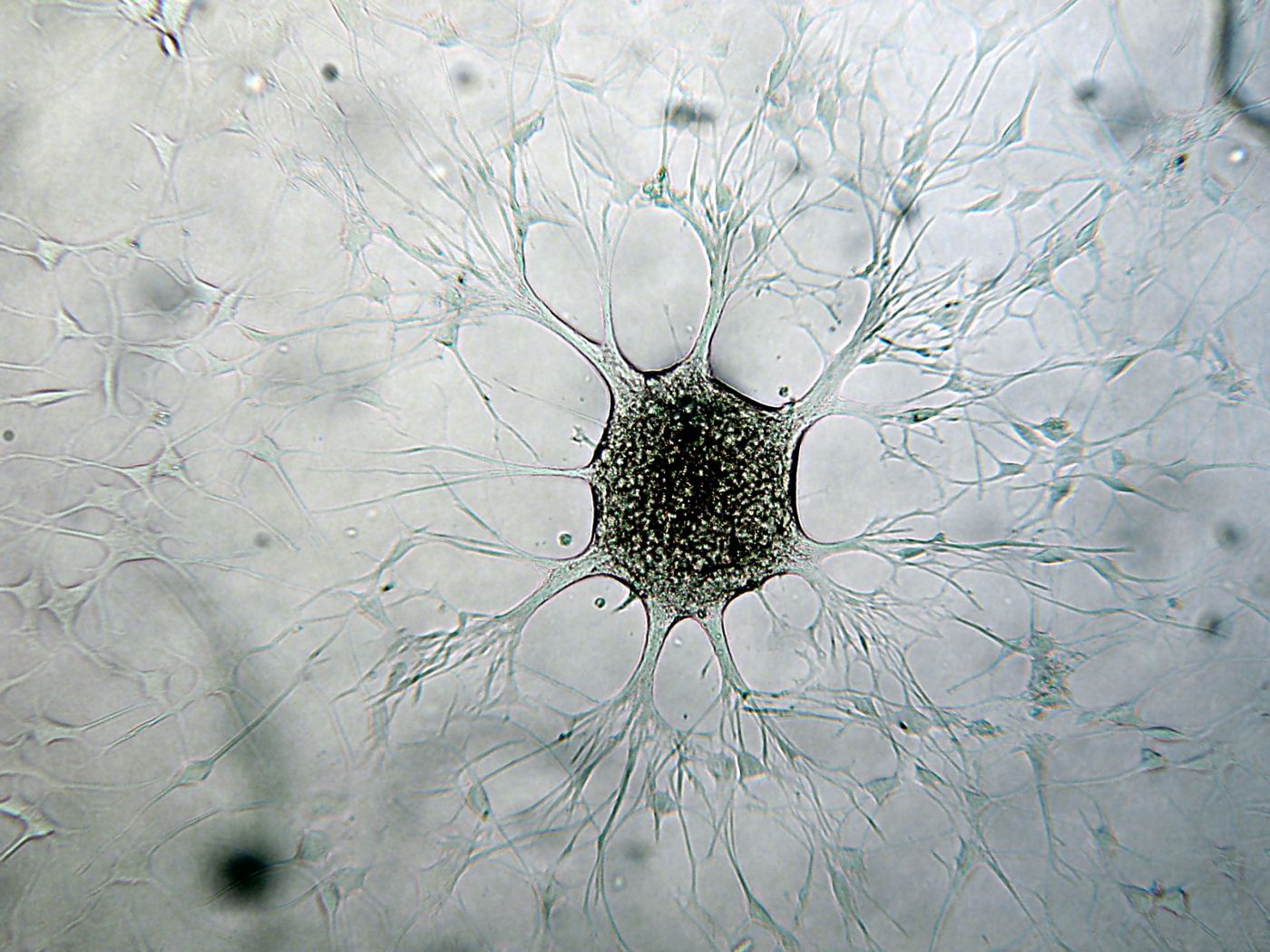

Header image: Glioblastoma cancer cell in culture. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Edited by Jessica Desamero

References

- Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015–2019. Neuro-Oncology. 2022;24(Supplement_5):v1-v95. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noac202

- von Bartheld CS. Myths and truths about the cellular composition of the human brain: A review of influential concepts. J Chem Neuroanat. 2018;93:2-15. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.08.004

- Zhang GL, Wang CF, Qian C, Ji YX, Wang YZ. Role and mechanism of neural stem cells of the subventricular zone in glioblastoma. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13(7):877-893. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v13.i7.877

- Greenwald AC, Darnell NG, Hoefflin R, et al. Integrative spatial analysis reveals a multi-layered organization of glioblastoma. Cell. 2024;187(10):2485-2501.e26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.03.029

- Bagley SJ, Logun M, Fraietta JA, et al. Intrathecal bivalent CAR T cells targeting EGFR and IL13Rα2 in recurrent glioblastoma: phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2024;30(5):1320-1329. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-02893-z

- Brown CE, Hibbard JC, Alizadeh D, et al. Locoregional delivery of IL-13Rα2-targeting CAR-T cells in recurrent high-grade glioma: a phase 1 trial [published correction appears in Nat Med. 2024 May;30(5):1501. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02928-5]. Nat Med. 2024;30(4):1001-1012. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-02875-1

- Choi, B. D., Gerstner, E. R., Frigault, M. J., Leick, M. B., Mount, C. W., Balaj, L., Nikiforow, S., Carter, B. S., Curry, W. T., Gallagher, K., & Maus, M. V. (2024). Intraventricular CARv3-TEAM-E T Cells in Recurrent Glioblastoma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 390(14), 1290–1298. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2314390

Leave a comment