Reading time: 6 minutes

Gracie Jennah Mead

Introduction

Exhausted T cells (Tex) were first discovered during chronic viral infections whereby the CD8 T cells (which are a type of immune cell that initiates killing of virally infected cells and cancerous cells) persist but can no longer clear the pathogen, this was first evident in HIV where the constant persistence of the virus led to a decline in function for these CD8 T cells [1]. The loss of functionality of these cells includes, lack of ability to proliferate after antigen recognition, reduced ability to produce effector cytokines and cytolytic molecules and also the inability to form functional memory cells [1]. So how does this relate to cancer? Well what cancer and chronic viral infections have in common is that they are both prolonged diseases which persistently express antigens. Chronic viral infection antigens can be gp120 on the HIV virus or tumour specific antigens which are encoded by genes specific to the tumour type that cause CD8 T cells to enter this dysfunctional state and ultimately become exhausted. The exhaustion causes a reduction in the ability of the immune system to attack the cancer cells and will ultimately lead to tumour progression.

Acute vs chronic T cell response

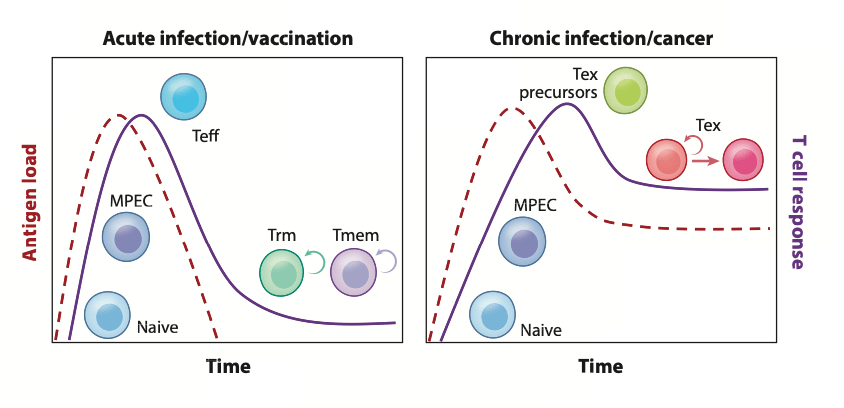

During cancer and chronic infections the antigen stimulation is constant due to the T cells not being able to clear the antigen and antigen always being present, this leads to a prolonged period of contact between the T cells and the antigen which leads to exhaustion and can be seen in figure 1. Whereas in normal situations during an acute infection the T cells will be in contact with the antigen long enough to achieve priming, activation, proliferation, clearing of the antigen after which the majority of T cells die or are kept for memory [2]. The clearance of antigen during acute infection is a tightly controlled process which is controlled by inhibitory receptors such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), T cell immunoglobulin mucin domain coating protein 3 (TIM3), lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3) and T cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT). These receptors prevent autoimmunity by downregulating the immune response which leads to resolution of the acute infection and allows memory formation once the antigen is cleared, and inhibitory receptors are also important for T cell exhaustion development.

Figure 1- Difference between acute and chronic infection t cell responses. Figure from [3]

Inhibitory receptors

Inhibitory receptors are very important during chronic infections and cancer as they are upregulated which causes T cell exhaustion and an insufficient immune response to resolve the chronic infection or cancer. During chronic stimulation T cells are primed and activated but not successfully due to either the lack of co-stimulation required for a fully activated and functional T cell or due to the level of inflammation present, causing the antigen to never be cleared and always be present [4]. This entails that the T cells will always be recognising the antigen but never clearing it, consequently, the T cells do not die and cannot be made into memory cells. To combat this the cells start to protect themselves by upregulating inhibitory receptors such as PD1, CTLA-4, TIM3, LAG3 and TIGIT, all of which play an important role in the hierarchal loss-of-function in T cells as well as the altered metabolism, which occurs during the exhaustion process [2].

How upregulation of inhibitory receptors leads to T cell exhaustion and cancer progression

When inhibitory receptors are upregulated, they will alter glycolysis, a key metabolic pathway which causes structural defects in the mitochondria increasing the reactive oxygen species production which causes a defect in another metabolic pathway called oxidative phosphorylation, consequently T cells cannot use this pathway to generate energy limiting the proliferation and functional ability of the T cells [5][6]. When all this is occuring, the T cell gradually loses important functions such as, IL2 production which helps to drive effector cell differentiation, loss of TNFa production which enhances T cell proliferation and cytokine production and finally the loss of interferon gamma production which is important for modulating immune responses, and enhancing killing by effector mechanisms. However, when the cells have reached terminal exhaustion, defined as T cells expressing high levels of multiple inhibitory receptors and loss of interferon gamma production and they can no longer effectively attack the tumour cells, this ultimately leads to an even more immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment and further tumour progression due to lack of cytotoxic killing [3]. Due to the implications exhausted T cells have on cancer progression, immune checkpoint inhibitors were developed to try and reinvigorate the exhausted T cells to combat.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been an important part of combating T cell exhaustion in cancer. As previously mentioned, a hallmark of exhausted T cells is the upregulation of inhibitory receptors. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been developed to bind to these receptors instead of its ligands essentially blocking the inhibitory effects that occur when the ligand binds its cognate receptor [7]. There is currently a vast range of mAbs which are in phase 3 clinical trials aimed at the inhibitory receptors and also five common mAbs used for PD-1 and CTLA-4 receptors in order to reinvigorate the immune response in the tumour microenvironment. CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade has been used in combination leading to a better response in patients, both these inhibitory receptors act on different parts of the cancer immune cycle.CTLA-4 acts during T cell priming and competes with costimulatory signals to inhibit priming and PD-1 acts to maintain peripheral tolerance prevent autoimmunity, since both these inhibitory receptors work in different phases of the cancer immunity cycle, it makes treatment more successful when dually blocking both anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1.

CTLA-4 inhibition

CTLA-4 inhibition or blockade uses a number of distinct mechanisms to reinvigorate the immune response when CD8 cells are exhausted. CTLA-4 competes with CD28, the positive co stimulatory molecule required for T cell activation, when CTLA-4 is present it induces more anti-inflammatory response due to inefficient T cell activation. However, blocking CTLA-4 allows CD28 to bind to the T cells enabling a second signal which is required for efficient T cell activation and thus sustaining T cell responses. In cancer this blockade means CD28 can efficiently activate T cells and allow for T cell responses to attack the tumour cells reinvigorating an immune response in the tumour. Another interesting mechanism which has recently been found is that blocking CTLA-4 allows the broadening of the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, diversifying the antigens which the TCR can recognise, meaning CTLA-4 blockade may allow antigens with low signal strength which aren’t normally sufficient to generate an effective T cell response to emerge. These antigens may be tumour specific antigens (TSA) such as neoantigen or tumour associated antigen (TAA) meaning that when CTLA-4 is blocked these antigens can be recognised by antigen presenting cells and generate an immune response mounted against the antigens thus increasing cancer immunity [8].

Conclusion

In summary, exhausted T cells have been an issue in cancer immunity due to their presence leading to a more anti-inflammatory tumour microenvironment where the T cells become less functional, have reduced memory formation and can cause tumour progression. Recent developments in immune checkpoint blockade has shown blocking the inhibitory receptors can cause a positive impact on the immunity within the tumour microenvironment and as seen by blocking CTLA-4 can reinvigorate the exhausted T cells. Overall there has been positive research coming from immune checkpoint blockade as a way to reverse T cell exhaustion and use it as a positive immunotherapy in cancer.

Edited by Maha Said

References:

[1] Dolina JS, Van Braeckel-Budimir N, Thomas GD, Salek-Ardakani S. CD8+ T Cell Exhaustion in Cancer. Front Immunol. 2021 Jul 20;12:715234.

[2] Jiang W, He Y, He W, Wu G, Zhou X, Sheng Q, et al. Exhausted CD8+T Cells in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment: New Pathways to Therapy. Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 2;11:622509.

[3] McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ. CD8 T Cell Exhaustion During Chronic Viral Infection and Cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019 Apr 26;37(1):457–95.

[4] Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends in Immunology. 2015 Apr;36(4):265–76.

[5] Watowich MB, Gilbert MR, Larion M. T cell exhaustion in malignant gliomas. Trends in Cancer. 2023 Apr;9(4):270–92.

[6] Huang Y, Si X, Shao M, Teng X, Xiao G, Huang H. Rewiring mitochondrial metabolism to counteract exhaustion of CAR-T cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Dec;15(1):38.

[7 ]Fares CM, Van Allen EM, Drake CG, Allison JP, Hu-Lieskovan S. Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Why Does Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Not Work for All Patients? American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2019 May;(39):147–64.

[8] Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discovery. 2018 Sep 1;8(9):1069–86.

Leave a comment