Reading time: 8 minutes

Alex DeWalle

At the core of translational oncology lies a fundamental problem: how do we kill tumor cells without harming healthy tissue? Novel therapies must directly target tumor cells to achieve this goal in a way that traditional chemotherapies cannot. CAR T-cell therapy (CAR T) is one of the most promising therapies in this regard, and could be among the most impactful developments in translational medicine this century – but CAR T faces many obstacles to achieving the levels of efficacy and widespread usage needed to truly become the standard of care. Scientists at Monash Institute of Medical Engineering in Melbourne, Australia are combining the fields of biomedical engineering, materials science, and translational oncology to develop a method of drug delivery for CAR T that could lead to huge improvements in treatment (1). Let’s explore their work and its ramifications.

CAR T is a powerful type of cancer immunotherapy which works by genetically altering the patient’s own immune cells ex vivo to attack an antigen expressed primarily by tumor cells (but not healthy ones) and then injecting the modified cells back into the body to kill tumors. This therapy solves many of the problems facing cancer therapeutics due to its potential for high tumor-specificity, but it still has obstacles related to delivering T-cells to the tumor site and keeping them there long enough to be effective. The researchers hope to overcome these obstacles with injectable micro-hydrogels, a drug-delivery tool that uses a gel to house CAR T-cells, allowing for better control of the cell delivery (2).

One of the most critical challenges to successful CAR T therapy is the method of delivering modified T-cells to the tumor site. CAR T has thus far been most effective against blood cancers, where reaching the tumor site is not a problem. But for solid tumors, effective delivery of T-cells to the tumor site can be challenging. Moreover, the immuno-suppressive tumor microenvironment makes it difficult for T-cells to proliferate, a critical part of effective treatment (3). These issues lead to low retention rates at the tumor site, resulting in reduced efficacy. Some treatments try to offset this inefficacy by using a high dosage of cells, a strategy that often exacerbates dangerous side-effects, such as “cytokine storms” or neurological damage (4).

That’s where injectable micro-hydrogels, a type of biomaterials-based delivery method, come in. By injecting a gel laden with modified T-cells directly at the tumor site, the treatment can be localized, increasing retention rates. The gel degrades slowly over time, allowing the T-cells to be released gradually to provide an extended response. T-cells may even proliferate inside the gel, improving the efficacy of treatment by replacing T-cells lost to the harsh tumor microenvironment (1). The injectable nature of micro-hydrogels has advantages over similar delivery methods like surgically implanted scaffolds, which are more expensive, more invasive, and less flexible for treating multiple metastases (1).

These researchers specifically evaluated a gelatin-based hydrogel for use in treating ovarian cancer. The T-cells were transduced to express chimeric antigen receptors (the CAR in CAR T) against a surface glycoprotein protein expressed almost exclusively by ovarian and some cancer cells called TAG-72. Ovarian cancer was an ideal treatment choice because it is typically detected in its later stages, and by the time of detection the cancer has often spread throughout the peritoneal cavity. Treating the metastases along with the primary tumor requires higher T-cell counts, resulting in more dangerous side effects – this, combined with the difficulty of delivering T-cells to the ovaries, makes ovarian cancer a strong candidate for this delivery method. By encapsulating T-cells in the hydrogel, doctors can inject them directly at the tumor sites and keep them there, and the protective nature of the hydrogel allows the T-cells to proliferate near the tumor for a sustained release. The result, in theory, is high efficacy and minimal side effects (1).

Here, the researchers were testing whether the T-cells would remain viable and effective after being embedded in the hydrogel for 7 days. Specifically, they evaluated the ability of T-cells to kill solid, three-dimensional tumor spheroids, as opposed to the typical two-dimensional monolayer of cancer cells that in vitro studies often use. These three-dimensional tumor spheroids better replicate the real tumor microenvironment (1). They also better mimic cancer stem cells, or cancerous cells that drive tumor progression and can form metastases. Cancer stem cells are a critical point of treatment, and often lead to the stubborn recurrence of tumors that makes treatment so difficult (5).

After encapsulating the T-cells in the hydrogel and allowing them to grow in T-cell media for 7 days, the T-cells were evaluated for cytotoxicity against tumor spheroids using a real-time cell analysis instrument. This instrument measures the change in electrical impedance between two electrodes, which depends on the number of cells attached to the well and the strength of that attachment. By measuring the changes in impedance after adding the T-cells, the death of the tumor cells in the spheroids could be measured. For additional confirmation, researchers used confocal microscopy to image T-cells recovered from the hydrogel killing the tumor cells in real-time over a 15 hour period.

The results demonstrated the robustness of the method. Not only did the cells survive the 7 days in the hydrogel (cell viability was 83% on day 1 and 88% on day 7) but they even proliferated by nearly 50% over that period (from 164 cells per microparticle on day 1 to 239 by day 7). The researchers also confirmed the functionality of the T-cells after encapsulation via flow cytometry, showing that their receptor expression was essentially unchanged (1).

The real-time cell analysis (RTCA) revealed the most impactful results. Researchers used several controls to isolate the impact of the hydrogel (“microgel” in the figure) on the T-cell’s effectiveness. First, they established a baseline reading of the cell index (the reading of the RTCA instrument) with just the cancer cells alone (the blue line in the figure). Then, they evaluated the effect of non-transduced T-cells, both added normally and added with the hydrogel (brown and pink lines). These served to control for the effect of the hydrogel itself, and to demonstrate the specificity of the modified CAR T-cells. Lastly, they evaluated the impact of the transduced CAR T-cells, both with and without the hydrogel (red and green lines). They tested these treatments against both ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR3 cell line) and breast cancer cells (Hs578T cell line).

Here are the biggest takeaways:

- The CAR T-cells were very specific to the OVCAR3 cells, which have high surface expression of the protein that the CAR T-cells are designed to target – TAG-72. They had meaningful but low efficacy against the Hs578T cells, but a much larger effect on the OVCAR3 cells, demonstrating high specificity.

- The CAR T-cells were highly effective at completely removing the OVCAR3 tumor cells in vitro. In less than 16 hours, complete or near-complete removal was observed based on RTCA results.

- The 7 days spent in the hydrogel seemed to have little-to-no impact on CAR T-cell efficacy. The CAR T-cells encapsulated in hydrogel were only marginally less effective compared to the CAR T-cells that were never encapsulated in hydrogel.

- The non-transduced T-cells had little-to-no impact on either cell line, demonstrating the need for antigen specificity in this treatment.

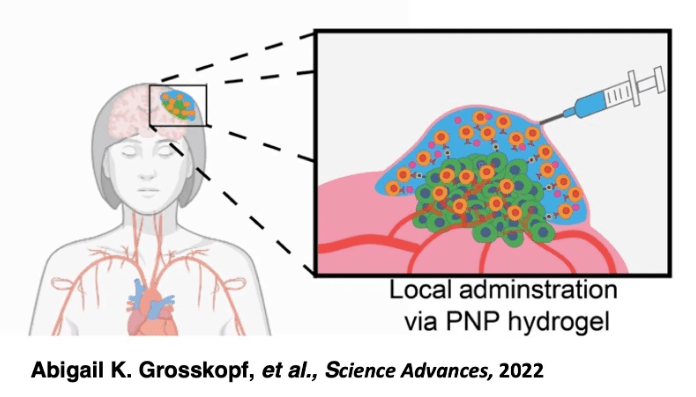

This paper demonstrates the strong therapeutic potential of CAR T-cell therapy as a treatment and injectable micro-hydrogels as a delivery method, but there’s still a long way to go before we see either become the standard of care. Specifically, in vivo testing will be needed to prove that the cytotoxic effects observed in vitro with this treatment-delivery combination can be replicated. Furthermore, the delivery method itself has room to be optimized, perhaps via parallel delivery of other molecules or cells to the tumor site. For example, Grosskopf et. al. demonstrated the value of infusing inflammatory cytokines into injectable hydrogels along with the CAR T-cells (6). Typical therapies involve delivering cytokines systemically to the bloodstream, but this can cause dangerous side effects. By delivering cytokines in the hydrogel, they were able to reduce unwanted side effects and increase the effectiveness of the therapy. Further research into parallel delivery of other therapeutics alongside CAR T-cells could prove promising. Regardless, these researchers have demonstrated the power of combining multiple scientific disciplines to craft an innovative treatment option, and the potential for future success in this therapeutic area is strong.

Edited by Nayela Chowdhury

Citations

- Anisha B. Suraiya, Vera J. Evtimov, Vinh X. Truong, Richard L. Boyd, John S. Forsythe, Nicholas R. Boyd, “Micro-hydrogel injectables that deliver effective CAR-T immunotherapy against 3D solid tumor spheroids”, Journal of Translational Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101477

- Li, J., Mooney, D. “Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery”, Nat Rev Materials 1, 16071 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.71

- Ueda, T., Shiina, S., Iriguchi, S. et al. “Optimization of the proliferation and persistency of CAR T cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells”, Nat Biomed Eng 7, 24–37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-022-00969-0

- Neelapu, S., Tummala, S., Kebriaei, P. et al. “Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy — assessment and management of toxicities”, Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 47–62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148

- Ayob, A.Z., Ramasamy, T.S. “Cancer stem cells as key drivers of tumor progression”, J Biomed Sci 25, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-018-0426-4

- Abigail K. Grosskopf et al., “Delivery of CAR-T cells in a transient injectable stimulatory hydrogel niche improves treatment of solid tumors”, Sci. Adv. 8 eabn8264 (2022) https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abn8264

Leave a comment