Reading time: 5 minutes

Hema Saranya Ilamathi

Viruses have long been associated with illnesses in humans, like the flu and AIDS, but many people are unaware that some viruses can be used to treat cancer. Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are natural or genetically engineered viruses that selectively target and destroy cancer cells. Using viruses to treat cancer originated in 1904 when cancer regression was observed after a patient got the influenza virus. Since then, multiple clinical trials have explored the potential of virus-based cancer therapy. However, difficulty controlling the virus’ pathogenicity has limited its application as a cancer treatment during those periods. After years of research, in 2015, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finally approved the first oncolytic therapy, T-VEC (talimogene laherparepvec), for the treatment of melanoma.

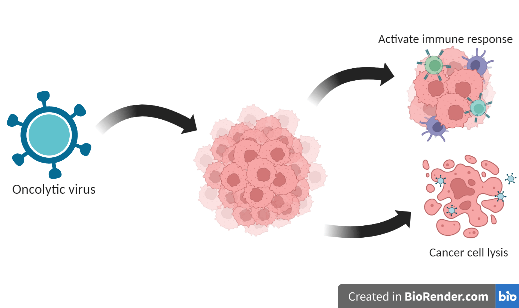

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are a powerful tool to fight cancer. Different naturally occurring viruses are genetically modified to increase their oncotropism, including Adenovirus, Herpesvirus, Parvovirus, Poxvirus, Semiliki Forest virus, Measles virus, Newcastle disease virus, Polio virus, Reovirus, and Maraba virus. Altered metabolism, suppressed immune response, genetic changes, and increased expression of specific cell surface receptors facilitate OVs’ to selectively infect the cancer cell. Upon infection, these viruses use the cell’s pathways to replicate, leaving fewer resources available to cancer cells for growth. At the same time, OVs activate cytotoxic pathways, leading to the rupture of cancer cells. In addition, releasing tumor-specific antigens from the destroyed cancer cells activates an immune response throughout the body. This way, an antitumor immune response is triggered in addition to the direct effect of killing cancer cells. Lastly, OVs damage the blood vessels that supply nutrients and oxygen to cancer cells, further contributing to cancer cell death. Altogether, OVs result in tumor regression and an overall improved immune response.

OV therapy offers several advantages compared to the traditional approaches to cancer treatment. OV replicates specifically inside cancer cells, where the immune response is weakened, minimizing potential off-target effects. Additionally, OV could be a great way to treat ‘cold cancers,’ where anticancer immune responses are suppressed. The multimode action of OV therapy also prevents the development of drug resistance, which is common among other cancer therapies. These promising properties of OV can be combined with other cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy. Clinical studies have found that combining OV with other treatments improves safety profiles and patient survival rates1,2.

Figure: Cancer cells are targeted by oncolytic viruses, resulting in their destruction and the release of tumor antigens. These antigens trigger an antitumor immune response, allowing the body to fight cancer more effectively. The virus is not scaleable. The image was created using BioRender.com.

OV therapy has unique challenges, such as the host antiviral immune response and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, that can limit OV entry. OVs can be delivered intravascularly or injected directly at the tumor site to reduce the host antiviral immune response. This makes OV therapy a potential treatment for skin cancer, although injecting OVs specifically at the tumor site is still difficult for other types of solid tumors. Researchers are investigating ways to improve OV bioavailability, such as by modifying their surface or encapsulating them in nanoparticles to target other solid tumors. Another challenge for OV treatment is their ability to cross the barrier (the tumor microenvironment) surrounding the cancer cells. However, the interaction between OVs and the tumor microenvironment is poorly understood. Some animal studies suggest that modulating the extracellular matrix, a supportive structure of proteins surrounding the tissues, may improve the virus’s spread.

T-VEC has overcome these challenges and is currently used to treat advanced melanoma. It is a genetically modified Herpes simplex virus (HSV) that targets cancerous melanocyte cells in the skin. Directly injected into tumors, it successfully bypasses the host antiviral immune response and is now being tested with immunotherapy. The most recent Phase II clinical trial revealed promising results when combined with Ipilimumab, which blocks the immunosuppressor molecule (CTLA-4) of T-cells3. Further clinical trials utilizing other OVs like reovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and coxsackie virus are currently being investigated to target different solid tumors.

OV therapy can potentially revolutionize cancer treatment when combined with other standard therapies. OVs have mild side effects compared to other treatments, including fever, chills, fatigue, headache, vomiting, anemia, and flu-like symptoms. Further research is needed to ensure the safety of this therapy and avoid any risk of releasing it into the environment. Also, effective anti-viral treatment procedures need to be framed following OV-based cancer therapy. With multiple OV-based cancer treatment regimens in clinical trials, more personalized treatment will be available for cancer patients in the future.

Edited by Shan Grewal

References

1. Rahman, M.M., and McFadden, G. (2021). Oncolytic Viruses: Newest Frontier for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 13. 10.3390/cancers13215452.

2. Cao, G.D., He, X.B., Sun, Q., Chen, S., Wan, K., Xu, X., Feng, X., Li, P.P., Chen, B., and Xiong, M.M. (2020). The Oncolytic Virus in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Front Oncol 10, 1786. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01786.

3. Chesney, J., Puzanov, I., Collichio, F., Singh, P., Milhem, M.M., Glaspy, J., Hamid, O., Ross, M., Friedlander, P., Garbe, C., et al. (2018). Randomized, Open-Label Phase II Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination With Ipilimumab Versus Ipilimumab Alone in Patients With Advanced, Unresectable Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 36, 1658-1667. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7379.

4. Tian, Y., Xie, D., and Yang, L. (2022). Engineering strategies to enhance oncolytic viruses in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7, 117. 10.1038/s41392-022-00951-x.

5. Li, K., Zhao, Y., Hu, X., Jiao, J., Wang, W., and Yao, H. (2022). Advances in the clinical development of oncolytic viruses. Am J Transl Res 14, 4192-4206.

6. Lauer, U.M., and Beil, J. (2022). Oncolytic viruses: challenges and considerations in an evolving clinical landscape. Future Oncol. 10.2217/fon-2022-0440.

Leave a comment