Reading time: 5 minutes

Charlotte Boyd

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small bubbles which are released from the cell. Cells produce multiple types of EVs which are different sizes ranging from approximately 30 nanometres to 10,000 nanometres. A nanometre is 10 million times smaller than a centimeter. This means that EVs are tiny and not visible by eye. We can visualize EVs using an electron microscope which uses electrons to generate high resolution images of very small biological specimens.

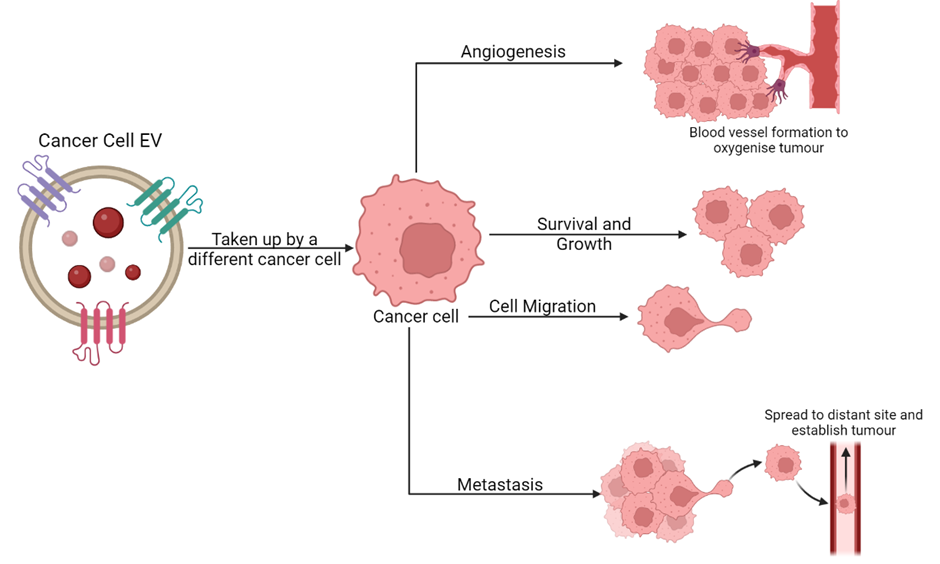

An EV is hollow and able to carry components, known as cargo, inside them (Image 1). Common cargo include protein, lipids (fat), DNA, and RNA. We can think of EVs as a communication device between cells. EVs are released from one cell and can be received by another cell. The EVs can fuse with the target cell membrane which encourages the EV to merge with the cell. This enables the transfer of cargo from one cell to another. There are also other ways in which the EV can be taken up by the recipient cell. On the surface of EV’s are proteins which are called surface proteins. The surface proteins can tell us what organ an EV originated from and promote fusion of the EV with the target cell.

EVs can be released into the space surrounding the cell. They are present in bodily fluids and waste such as saliva, urine, blood and faeces. EVs are found in both healthy individuals and diseased individuals. This provides us with a unique opportunity to be able to study the differences in EV cargo, production or uptake in diseased and healthy individuals. By studying the difference in these factors, it may provide us with an insight into the disease.

What are EV’s Role in Cancer?

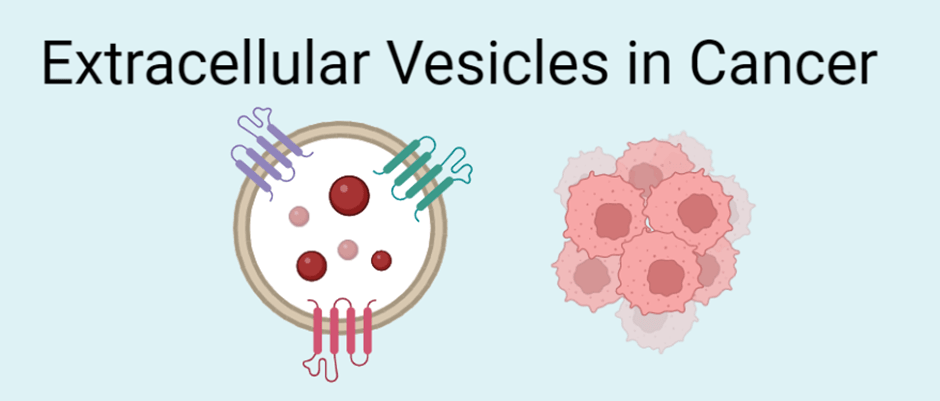

EVs have been linked to numerous roles within cancer (Image 2). Researchers have found that EVs can promote cancer progression. Cancer cells survive in poor conditions where there is a lack of nutrients and oxygen to grow. The exchange of EVs between cancer cells may enable the passing of important and potentially beneficial cargo to other cancer cells. The transfer of EVs under these stressful conditions may promote the survival and growth of these cancerous cells.

To combat the lack of oxygen, EVs have been known to promote tumor angiogenesis which is the formation of new blood vessels. Without sufficient oxygen, tumor size is halted at 1-3mm as the cells must respire to survive. The generation of new blood vessels promotes cancer cell growth and even spread of cancer throughout the body as rogue cancer cells can enter the bloodstream and spread within the body. There are drugs designed to prevent angiogenesis (anti-angiogenics) which work by preventing blood vessel formation and starving the tumor of oxygen killing it. However, such molecules may not always succeed in targeting EV-promoted angiogenesis. Indeed, one study found that EVs secreted by triple negative breast cancer cells contain cargo that can bypass an anti-angiogenic drug and still promote blood vessel formation (Feng et al. 2017).

EVs are also known to play a role in the spread of cancer to distant organs within the body. This process of cancer cells entering the bloodstream, finding a secondary site with optimal conditions and forming a tumor there is known as metastasis. EVs have been seen to help promote metastasis at multiple stages throughout. To begin with, EVs produced by an aggressive glioblastoma (brain cancer) cell line from cancerous cells have been seen to promote cell migration properties of hamster ovarian cells (Christianson et al. 2013). Cell migration is one of the first steps in metastasis as the cell needs to move towards the blood stream so it can travel to a distant site. EVs have also been seen to contain components which break down any obstacles in the way of the cancer cell and promote the formation of a path for cancer cells. This helps them to get into the bloodstream allowing them to metastasise to a distant site.

It is clear to see that EVs are involved in every aspect of cancer progression from promoting survival to mediating metastasis. However, there are a few ways in which researchers are fighting back by utilizing these EVs in an alternative way.

How can EVs be used in Cancer Research?

EVs are very versatile. As they are small bubbles with a hollow inside this implies that we may be able to use them to our advantage in fighting cancer. One method of using EVs is putting a drug inside them, this is called drug loading. By loading an anti-cancer drug into EVs, this could one day be used as a treatment strategy for cancer. We could harvest a patient’s EVs using a blood sample, load them with an anti-cancer drug then put them back into the patient. An advantage of this is that the EVs have come directly from the patient so there should not be any rejection from the body. However, this personalized medicine, although years off, would be very expensive and we cannot guarantee that it will get to the tumor and release the drug. Instead, it may be better to engineer EVs derived from other cells (not directly from the patient), target them to the tumor and initiate drug release.

Recently, we have been able to locate where an EV has come from within the body (Dash et al. 2022). This is promising for cancer research as we would be able to study EVs which have come directly from the bowel if the patient is suffering with bowel cancer. Through collecting these EVs and investigating what cargo is inside them this could provide information on how the cancer is progressing and may provide an insight into what we can do to target EVs produced by cancer cells.

Another potential use of EVs is as biomarkers for early cancer detection. A biomarker is a naturally occurring molecule which can discriminate between healthy and disease state. One study found that two specific surface proteins on an EV could be utilized as biomarkers for detecting early-stage colorectal cancer (Dash et al. 2022). Further investigation is needed to see if there are biomarkers which could be identified to diagnose other cancers.

Extracellular vesicles are very small packets of information which have huge potential in deciphering complex diseases. More research into their potential for cancer treatment and diagnosis is needed.

Edited by Tala Tayoun

The information in this article is from the following reviews and articles:

Chang, W. H., Cerione, R. A., & Antonyak, M. A. (2021). Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Cancer Progression. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2174, 143–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0759-6_10

Christianson, H. C., Svensson, K. J., van Kuppevelt, T. H., Li, J. P., & Belting, M. (2013). Cancer cell exosomes depend on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans for their internalization and functional activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(43), 17380–17385. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1304266110

Dash, S., Wu, C. C., Wu, C. C., Chiang, S. F., Lu, Y. T., Yeh, C. Y., You, J. F., Chu, L. J., Yeh, T. S., & Yu, J. S. (2022). Extracellular Vesicle Membrane Protein Profiling and Targeted Mass Spectrometry Unveil CD59 and Tetraspanin 9 as Novel Plasma Biomarkers for Detection of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers, 15(1), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010177

Feng, Q., Zhang, C., Lum, D., Druso, J. E., Blank, B., Wilson, K. F., Welm, A., Antonyak, M. A., & Cerione, R. A. (2017). A class of extracellular vesicles from breast cancer cells activates VEGF receptors and tumour angiogenesis. Nature communications, 8, 14450. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14450

Liu, S. Y., Liao, Y., Hosseinifard, H., Imani, S., & Wen, Q. L. (2021). Diagnostic Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 9, 705791. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.705791

Wu, M., Wang, M., Jia, H., & Wu, P. (2022). Extracellular vesicles: emerging anti-cancer drugs and advanced functionalization platforms for cancer therapy. Drug delivery, 29(1), 2513–2538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2022.2104404

Zaborowski, M. P., Balaj, L., Breakefield, X. O., & Lai, C. P. (2015). Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. Bioscience, 65(8), 783–797. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv084

Leave a comment