Reading time: 6 minutes

Karli Norville

It can take more than ten years to move a drug or therapeutic from discovery to FDA approval. Despite the years of research put in before a clinical trial begins, many therapeutics fail due to unforeseen safety complications or their lack of efficacy. Why do so many fail? Despite researchers’ best efforts to build safe and efficacious new therapeutics that will succeed in human trials, there’s no getting around the fact that our best pre-clinical models and our most reliable cell culture methods are simply…not humans.

Before clinical trials begin, therapeutics are evaluated in pre-clinical models. Even the best model system is going to differ from a human patient in some way. Models grown in labs such as cell cultures or organoids are too isolated to allow researchers to predict how well the drug may disperse around the body, or whether the drug has potential side-effects on other organs. Mouse models (discussed previously on OncoBites here) have proven absolutely invaluable for all of biomedical research, including cancer research. There are a large number of well-established mouse tumor models which allow researchers to interrogate different tumor types and to screen potential drug targets. Mouse tumor cell lines implanted into mice are relatively simple and inexpensive and can allow researchers to perform proof-of-concept experiments in a replicable context. But these models are ultimately constrained by differences between species and the homogeneity of tumor cell lines. Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs), in which mice have been engineered to have certain mutations which cause specific cancers, can provide insight into the early stages of cancer and how cancer may progress or respond to treatment. Again, however, these models are limited to certain cancer types and by differences between species.

Patient-Derived Xenografts

Is it possible to make a mouse tumor model more like a human patient? One creative solution is the relatively recent rise of Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) models. A xenograft is the process of implanting tissue – or tumors – from one species into another. PDX mouse models are systems wherein a tumor removed from a human patient has been implanted into an immunocompromised or humanized mouse host. These mice either lack a functional immune system or have been engrafted with human immune cells. These manipulations of the immune system allow the human tumors to grow without being attacked by mouse immune cells, which would immediately recognize the human cells as “non-self” and destroy them. PDX models provide an opportunity to study tumor biology as well as the efficacy of preclinical drugs and therapeutics in a system with a fully human tumor and oftentimes, human immune cells.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of using PDX models

PDX models offer several advantages over other available models. First, PDX models utilize human tumor cells. This allows human biology to be studied directly, rather than extrapolating data from mouse tumors. PDX models are additionally in vivo systems, meaning that the biology is studied in the context of a whole living organism, rather than just in laboratory culture (in vitro). In vivo systems often provide researchers with insights that are more likely to be similar to conditions found in humans than using in vitro models.

Second, PDX models can retain the heterogeneity of human tumors. Human tumors consist of a wide variety of tumor cells. While they all belong to the same cancerous growth, many of the cells have accumulated unique mutations. Thus, a wide variety of tumor cell types exist within a single tumor, with varying susceptibility to different therapeutics. This is one reason cancers can be difficult to treat. Tumor models utilizing human cancer lines, though human derived, fail to replicate this heterogeneity, as all the cells in these models are exactly the same. As PDX models retain heterogeneity seen in patient tumors, this allows researchers to actively evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of new drugs, the biology of tumor mutations over time, and tumor resistance to treatments.

Third, by implanting pieces of tumor from human patients, the tumor stroma, or the elements of a solid tumor which are non-tumor cells such as endothelial cells or fibroblasts, can be maintained for at least the first few times the tumor is taken from one mouse and implanted in a new one to continue the line. The stroma helps form the scaffolding, or extra-cellular matrix (ECM) and can contribute to the slurry of signaling molecules in the tumor microenvironment (TME) that contribute to tumor growth. The ECM and the make-up of the TME can heavily influence how the tumor cells themselves grow, but also how the vasculature forms, how well immune cells can function, and what nutrients are available to both tumor cells and non-cancerous cells. Compared to human cell line models or even spontaneous mouse models such as the GEMM, PDX models provide superior insight into the workings of a human tumor within the context of a fully human stroma and immune system.

Although PDX models have many advantages over conventional tumor models, PDX models are not without their challenges. Establishing a PDX of the cancer type of interest can prove difficult, and some human cancers fail to establish in all but very specialized mouse strains. PDX models also require a lot of maintenance. Unlike a cancer line which can be maintained in cell culture, PDX models are typically maintained in mice, requiring consistent monitoring of tumor growth and establishment of the tumors into new hosts or into liquid nitrogen repositories for long-term storage. PDX models are therefore often extremely costly and time-consuming, which limits their utility.

Looking Forward

PDX models have been successfully established for many cancer types including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer. These models are helping investigators better understand the biology of how these tumors progress and what therapeutics they may respond to. Some investigators are also looking to utilize PDX models in the world of personalized medicine (discussed previously on OncoBites here), in which “Avatars” are being created for individual patients. The researchers can screen the host of available treatment options, singly and in combination with each other, to determine which may be the most effective for the patient. Additionally, they can “preview” how the patient’s own tumor may mutate to resist certain treatments. Although still in early stages and quite experimental, this type of work opens up exciting possibilities for determining patient treatment regimens in the future.

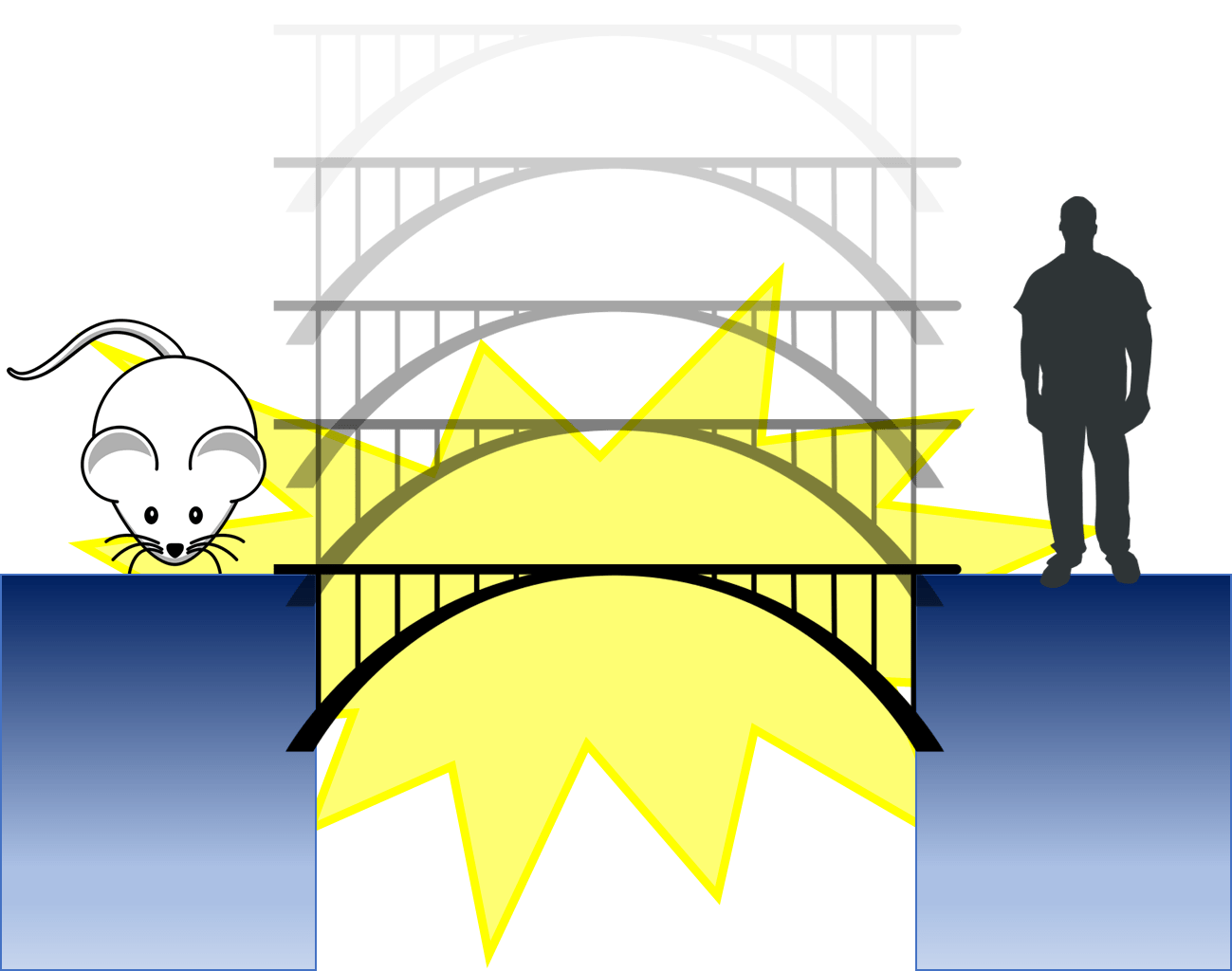

We are always going to have to make the jump from pre-clinical models into humans in the clinic, and there will always be unknowns. But PDX models are one way we are bridging the gap between the two, turning a risky leap into a more manageable step across the gap.

Edited by Emily Chan

References

- Hughes JP, Rees S, Kalindjian SB, Philpott KL. Principles of early drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Mar;162(6):1239-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. PMID: 21091654; PMCID: PMC3058157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3058157/

- Abdolahi S, Ghazvinian Z, Muhammadnejad S, Saleh M, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Baghaei K. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, applications and challenges in cancer research. J Transl Med. 2022 May 10;20(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03405-8. PMID: 35538576; PMCID: PMC9088152.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9088152/

- Okada S, Vaeteewoottacharn K, Kariya R. Application of Highly Immunocompromised Mice for the Establishment of Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models. Cells. 2019 Aug 13;8(8):889. doi: 10.3390/cells8080889. PMID: 31412684; PMCID: PMC6721637. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6721637/

- Jung J, Seol HS, Chang S. The Generation and Application of Patient-Derived Xenograft Model for Cancer Research. Cancer Res Treat. 2018 Jan;50(1):1-10. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.307. Epub 2017 Sep 13. PMID: 28903551; PMCID: PMC5784646. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5784646/

- Malaney P, Nicosia SV, Davé V. One mouse, one patient paradigm: New avatars of personalized cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2014 Mar 1;344(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.10.010. Epub 2013 Oct 22. PMID: 24157811; PMCID: PMC4092874. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4092874/

- Mouse clipart from https://publicdomainvectors.org/

- Human and bridge clipart from Wikimedia Commons

Leave a comment