Reading time: 4 minutes

Ian Lock

By directing immune cells to attack tumor cells, immunotherapy uses the body’s own biological mechanisms to target and eliminate cancer. Recently this concept has been retooled for another class of therapeutics that capitalizes on a cell’s internal processes to target cancer cells.

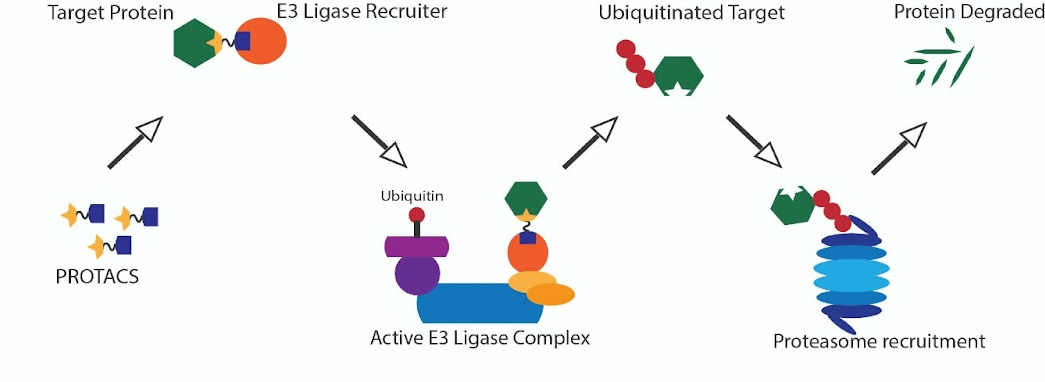

PROTACs or proteolysis-targeted chimeric molecules are of immense interest in their capability to target and degrade proteins essential for cancer cells’ function. The molecular basis of this technology resides in the system of protein stability and degradation reliant on ubiquitin tagging and transport to the proteasome. Ubiquitin is a small protein that is attached to target proteins acting like a flag recognized by the transport machinery. Following the attachment of one or more ubiquitin tags on a target protein, this protein is shuttled to the proteasome, where the protein is unfolded and broken down into its constitutive peptide parts. PROTACS use ligands or hooks to bring together a specific ubiquitin-attaching protein and the target protein facilitating the ubiquitin attachment and degradation of the target.

Ubiquitination, however, is just one of the 400 alterations that are utilized by a cell to change protein function. These alterations are called post-translational modifications (PTMs). Not only do each of these alterations have specific functions, but their positions on a protein and the number of modifications at that position (ex., mono vs. poly ubiquitination) also affect the resulting function of the protein.

To illustrate this complexity, we will use the tumor suppressor protein TP53. Following DNA damage, hypoxic stress, or oncogene activation stress, TP53, which is normally present in small amounts, is stabilized, and the protein level in those cells increases. One stabilization method is phosphorylation, and one is poly-ubiquitination by the protein FATS. Stabilization can lead to a number of responses ranging from temporary growth arrest to cell death. While polyubiquitination by FATS can lead to stabilization, when TP53 is mono-ubiquitinated by MDM2 or poly-ubiquitinated by MUL1, it is degraded via the proteasome. This is part of a feedback loop that allows TP53 to function, such as stopping the cell cycle for DNA damage repair to occur when necessary but downregulating TP53 short of inducing cell death.

To capitalize on the anti-cancer effects of the TP53 protein, Liu et al. use a DUBTAC approach to stabilize TP53. The inverse of PROTACs, DUBTACs, or deubiquitinase targeting chimeric molecules stabilizes proteins by removing a ubiquitin tag. This is especially encouraging for about 1.2% of cancers that contain an amplification of the ubiquitin ligase MDM2 that targets TP53 for degradation. In these cells, over-ubiquitination of the TP53 protein allows for cells to bypass growth checkpoints and become malignant.

This is only one example of the expanse of protein targets whose specific modification could be used to treat many cancer-causing abnormalities in different body parts. In recognition of this complexity, there is an ever-expanding repertoire of proximity-modifying drugs or drugs that capitalize on these internal modification processes to alter the target protein’s function (1). Beyond the examples of ubiquitination covered above, other types of post-translational modifications that can be leveraged for protein regulation include phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and acetylation (2–4).

But why are these proximity-modifying drugs so exciting for the field of cancer treatment?

The first reason is the expansive number of targets that can be modified to affect cancer cells and the specific targeting that is achievable using different “hook” combinations. Approximately 600 known E3 ubiquitin ligases, 540 kinases, 200 phosphatases, and 30 known histone acetyltransferases exist. Each of these proteins is expressed in different amounts and in different tissues. Selection of the appropriate post-translational modification in the right tissue allows for reduced toxicity (5,6).

The second reason is drug delivery. A constant difficulty in cancer therapy is delivering enough compounds to impact the cancer cell. Because many of these DUBTACs and PROTACs are recycled to target another target protein, the amount of drug necessary to have an effect is reduced.

While there are still significant difficulties ahead in selecting the right hooks for the optimal PTM catalyzing protein and the right ligands for the target proteins, proximity modifying drugs are an incredible advance in cancer therapy with a promising future in the clinical setting.

Edited by Anthony Tao

References

Yan S, Qiu L, Ma K, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Li X, Hao X, Li Z. FATS is an E2-independent ubiquitin ligase that stabilizes p53 and promotes its activation in response to DNA damage. Oncogene. 2014;33(47):5424–33.

Liu J, Yu X, Chen H, Kaniskan HÜ, Xie L, Chen X, Jin J, Wei W. TF-DUBTACs Stabilize Tumor Suppressor Transcription Factors. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(28):12934–41.

Henning NJ, Boike L, Spradlin JN, Ward CC, Liu G, Zhang E, et al. Deubiquitinase-targeting chimeras for targeted protein stabilization. Nat Chem Biol. 2022;18(4):412–21.

Willson J. DUBTACs for targeted protein stabilization. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(4):258.

Zhang P, Zhang X, Liu X, Khan S, Zhou D, Zheng G. PROTACs are effective in addressing the platelet toxicity associated with BCL-XL inhibitors. Explor Target Anti-tumor Ther. 2020;1(4):259–72.

Sacco F, Perfetto L, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. The human phosphatase interactome: An intricate family portrait. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(17):2732–9.

Images adapted from:

Promega, Chem UCLA

Emamzadah S, Tropia L, Vincenti I, Falquet B, Halazonetis TD. Reversal of the DNA-binding-induced loop L1 conformational switch in an engineered human p53 protein. J Mol Biol. 2014 Feb 20;426(4):936–44.

RCSB PDB – 2N1V: Solution structure of human SUMO1 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2n1v

Leave a comment