Varshit Dusad

Imagine a dystopian world. Here, some citizens of an otherwise well-functioning state have gone rogue and are running an anti-national agenda. They are always plundering the natural resources meant to be evenly distributed among the population. They are quite cunning as they start slowly by deviating from the laws of their natural order and silently recruit other members in their liege. When they have secured enough people and arms they start aggressively attacking their own country, taking control of natural resources, developing new infrastructure to support their needs, and generate huge pollution that hurt others indirectly. When they are done, they mobilize to another country to satisfy their greed and cause another round of havoc.

Of course, the state does not keep quiet. It is patrolled by an allied world security force which aims to ensure any threat is quickly neutralized. However, they are often late to take appropriate action. The insurgents become large in number and hide within the population making it difficult to distinguish between them and civilians. The security force happens to be augmented with special detection devices to identify these terrorists selectively and weapons are upgraded to deal with the threat. However, innocent civilians end up being killed as collateral damage.

This is obviously unacceptable!

Yet, the world security council is left wondering what to do…

The above story is not a retake on the current geopolitical climate. Rather, it is a telling of a very personal and intimate story one in every three of us experiences. It is the story of the struggle with cancer. As you might have guessed, the insurgents are cancer, the world your body, the state is the tissue/organ where cancer first appears and the armed forces are our immune system.

Cancer is a malevolent beast hiding under the sheep’s cover until it strikes with full force. It proliferates excessively taking surrounding resources in, causes angiogenesis and reshapes the environment making it anoxic and difficult for normal cells to survive. The immune system tries its best but despite many differences with civilian cells, it is notoriously hard to differentiate cancer cells.

Scientists have recently come up with an effective strategy to combat cancer cells in the form of CAR-T therapy. Here, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is introduced artificially into T-cells of the immune system (thus, CAR-T). This “upgrades” the T-cells with the potential to selectively differentiate cancer cells from normal cells and then kill them. It has been very effective and is many therapies based on it are currently undergoing a clinical trial. For example, Belgian Biotech company Ceyland has recently received its FDA approval for exploring a CAR-T therapy clinical study, using cells from donors, unlike conventional approved therapy that exploits patient’s own cells.

However, CAR-T therapy is not without its pitfalls. First, it relies on a chance encounter of T-cells and cancer cells, which can reduce clinical effectiveness. Second, the engineered immune cells often bring risks such as cytokine release syndrome, macrophage activating syndrome, and neurotoxicity. This causes collateral damage to healthy and functioning cells that overall harm the human body.

The risk of severe side effects requires novel therapeutic strategies to harness the benefits of CAR-T therapy while minimizing the collateral damage. However, unlike the world security council in our story who is still pondering about solutions in a typical bureaucratically inefficient manner, researchers are finding answers that may make CAR-T therapy safer. Their ideas are as creative as they are innovative and may help to reverse the dystopian outcome experienced by patients.

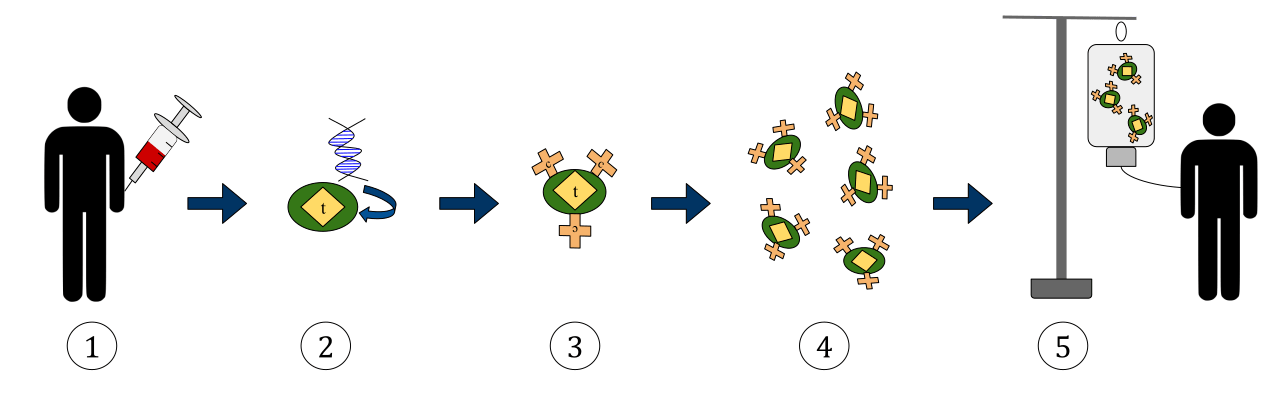

One of the latest advancements comes from Martin Fussenegger and colleagues who have developed a novel idea to augment CAR-T therapy. In a study published last year, they constructed a novel bioengineered system which utilizes non-immune cells such as HEK-293T and human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Both of these are naturally attracted towards cancer cells. They developed a novel system in these cells using a complex design utilizing proteins from a variety of different sources.

First of all, the surface of these cells is padded with artificially designed antigen receptors (also called Chimeric antigen receptor or CAR) regions added onto the top of immune sensors, known as interleukin receptors or ILRs to identify and attack the cancer cells. Originally, the system remains in an off-state when the receptors do not make any contact with cancer cells’ surface. But when they do, they start a signaling cascade using the JAK-STAT signaling mechanism. This results in expression of a special enzyme which has the property to move across the cell membrane and then catalyze a prodrug (a non-toxic substance) into a toxic drug which results in the death of cancer cells.

Here’s how it all comes together. You deliver a non-toxic form of a cancer drug into the patient and simultaneously inject the modified versions of naturally occurring cells. These cells are naturally attracted to cancer, sense them and produce an enzyme which converts the “prodrug” into “the drug” killing the cells. This removes the cross-fire damage caused by T-cell therapy while at the same time improves target specificity of drugs by ensuring they are active only when in the vicinity of cancer cells and specifically kill them.

It may sound like magic from that dystopian world but it’s real. The secret lies in the design of a bio-molecular switch Fussenegger and colleagues designed.

The switch is a protein cluster comprising of differentiation 43 external and 45 internal proteins and is known as CD43extCD45int. When the cell is floating freely, this molecule stays in close proximity to the ILRs and shutting down any signal propagation from JAK-STAT kinase, thereby maintaining the “off” stage. But when the cell touches another cell, CD43extCD45int is pushed away from the JAK-STAT kinase allowing it to signal that ILRs have recognized cancer and the special enzyme needs to be expressed thus turning “on” the switch. The special enzyme is known as uracil phosphoribosyltransferase, or FCU1, which is a conjugate of cytosine deaminase. This enzyme can change a nontoxic prodrug such as 5-fluorocytosine or FC into a toxic chemical capable of killing the cell such as 5-fluorouridine monophosphate, or FUMP.

The second “magical” step is to ensure FCU1 is transported only into the adjacent cancer cell. This is accomplished by attaching a protein to FCU1 known to traffic in between adjacent cells. It’s known as herpesvirus protein VP22 but usually just called VP22. The segregated Cd43extCD45int allows ILRs to recognize CARs and signal for FCU1 to be made and sent to via VP22 into the target allowing FC to turn into FUMP and killing it.

Despite its complexity, as the team reveals, the switch is effective and shows the potential to prevent collateral damage and other adverse events in cancer therapy inside lab investigations. However, further work needs to be done to explore the applicability in clinical settings.

Cancer has been a deceptive and dangerous disease for many reasons. Unlike pathogen-caused illnesses, it arises from malfunctions inside healthy cells. These are harder to detect and may not be fully recognized until the problem becomes severe. While many cancer-killing agents are available in lab conditions it is identifying “cancer only” toxic drugs and then ensuring their safe and efficient dose to tumor sites which have been obstructing the cure of cancer. After all, when it comes to killing cancer, even a bullet might suffice but it may kill the patient as well). The task of finding the magic silver bullet which kills the target without harming the general population has become the holy grail of cancer research. Hopefully, with advancements such as this switch, advances in CAR-T and CAR-non immune cells-mediated therapy will realize that goal so we can avoid dystopia and bring cancer’s anarchy to an appropriate halt.

Work Discussed

Kojima, R., Scheller, L. & Fussenegger, M. Nonimmune cells equipped with T-cell-receptor-like signaling for cancer cell ablation. Nature Chemical Biology 473, 42-51 (2017).

What would you suggest trying to do to everyone?

LikeLike